ESPACIO DESPACIO

ESPACIO DESPACIO

RECENT WORK BY ALBERT LÓPEZ, JR.

February 7, 2022 – March 31, 2022*

ARTIST TALK: March 7, 2022 @ 6PM (via Zoom)

After nearly two years closed to the public, Cerritos College Art Gallery is pleased to finally reopen its doors with an exciting solo exhibition featuring a new body of work by Santa Ana-based artist, Albert López, Jr. While previous projects by López have included high-energy performances - dragging a van behind him in the street, rhythmically cutting taco meat to the beat of a live DJ, and giving out dollar dances to gallery visitors - his recent work focuses on slowing things down (hence the title of the exhibition) in order to create an atmosphere of quiet contemplation. In keeping with López’s established practice, however, these new works continue to invoke his distinctive punk povera aesthetic, elevating simple, everyday materials – such as repurposed wood, plexiglass, and LED bars or polyvinyl sheeting, florescent lights, and plastic buckets - into visually-stunning, as well as surprisingly-nuanced, conceptual assemblages.

The primary inspiration for this recent body of work is the artist’s hometown of Santa Ana. Situated within the heart of historically-conservative Orange County, Santa Ana is a predominantly Latino city that has maintained a strong sense of comunidad despite decades of over-policing and ongoing attempts at cultural erasure. López’s assemblages allude to these tensions through multiple aesthetic, symbolic, and textual references. Perhaps the most prominent of these are the repeated overlapping vertical and horizontal forms, variously made from glowing LED bars and window-like cut outs, which come directly from the brutalist architecture of the Orange County Jail in Santa Ana, specifically its fortress-like slit windows. Nicole R. Fleetwood, in her important study on prison art, Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration, coined the term carceral aesthetics to describe how prisoners, “out of the state’s designation of them as social failures,” assemble their art from “wreckage and violence.” López’s appropriation of this distinctive feature of the well-known building, recognizable to many locals, highlights the prominent placement of the county jail within the city of Santa Ana itself, and therefore its regressive hold on the mental state of the people that live there, transforming even those on the outside of its walls into de facto carceral subjects. At night, the iconic vertical and horizontal windows of the jail glow with light, dominating the Santa Ana skyline, and, during the day, they become blank voids from the outside; while inside, for the prisoners, they provide a brief, but inaccessible, view of the outside world. One of the ways López plays off of this reversibility is through the use of one-sided plexiglass, whereby viewers can functionally peer through the windows in his hand-built architectonic structures from one angle, but not from another. Of course, this kind of one-way window is itself a familiar feature of prison infrastructure, used by police and prison guards to gaze undetected at suspected criminals and convicted felons alike. However, in López’s assemblages, the position of the viewer is never really stable, as simply moving around the structures alternately places them on both sides of a surveillant system. From one vantage point, for example, visitors can peer through a one-way window cut into a make-shift wall at the large plexiglass sign mounted on the far side of the room, itself back-illuminated by glowing LED bars oriented in that recognizable prison-inspired cross-formation, only to be chastised for their scopophilia by the word, ‘METICHE’ (Spanish for ‘nosy’), inscribed there in one of the gothic-style fonts made popular by Mexican-American graffiti and tattoo artists.

In an adjacent installation, Fantasía Sistémica, the artist assembles a row of custom lenticular prints to create the illusion of a chorus line of alebrije mosquitoes flapping their wings as the viewer moves past. As with most of Lopez’s references, however subtle, the choice of mosquitoes is deliberate here. Notoriously unwanted pests, mosquitoes are typically treated as an invasive species in need of eradication, evidenced by the mass dispersal of insecticides overseen by municipal mosquito control programs throughout Southern California. In another nearby illuminated plexiglass sign, López inscribes the words ‘WEED’ and ‘SEED,’ a call out to a different kind of eradication plan, the infamous Weed and Seed Program, established by the Department of Justice’s Community Capacity Development Office in 1991, ostensibly to reduce drug and gang violence in “high-risk” neighborhoods, communities that almost inevitably were made up of people of color, through heavy policing and frequent arrests. Targeted as it was at historically-oppressed racial and ethnic enclaves, including Santa Ana, the Weed and Seed Program was more than just a mechanism to extend the penal system into the wider community, it also served as a precursor to today’s gentrification, breaking down local culture by disrupting communal integrity. The fact that López’s previously-mentioned mosquitoes are also brightly-colored alebrijes, a kind of folk art sculpture commonly associated with Mexican and Mexican-American culture, further interrogates the racial, ethnic, and cultural implications of such governmental interventions into regional population control, while simultaneously acknowledging and celebrating the ability of those threatened communities to persist in the face of powerful systemic pressures.

Because of the thoughtful analysis of social concerns that permeate these works, it might be tempting to see them solely through a political lens. However, the art historical references are just as profound and, in fact, not, for López, unrelated. As Fleetwood has argued, the prison and the museum are two sides of the same coin; each constructing a societal ideal – one positive and the other negative – around existing racial, ethnic, and class associations. In a perfect example of this, the brutally-minimal Orange County Jail was completed in the late 1960s, at the same time that Minimalism, and the related Light and Space Movement, dominated the local Southern California art scene. In fact, a number of prominent Light and Space artists taught at the then-newly established UC Irvine MFA program and graduates from that program, including Chris Burden and Nancy Buchanan, founded the important Conceptual art gallery, F-Space in (where else?) Santa Ana. As himself a graduate of UCI’s MFA program, as well as a native of Santa Ana, López rightly views himself as a generational descendant inheriting from all the region’s contemporary art and cultural traditions. This is why, in his ongoing praxis, López seeks to breakdown the kind of unspoken culturally-coded assumptions that would, for example, bracket rasquachismo from similar art historical practices, such as assemblage and the readymade. López’s paintings of melting pink popsicles are an homage to the fresa con leche paletas sold by local pushcart street vendors, as well as a nod to Pop artists, such as Wayne Thiebaud and Claes Oldenburg. His use of glowing LED bars references the slit windows of the nearby jail, but also calls back to the illumination-based works of Light and Space artists like Robert Irwin and Dan Flavin. Finish Fetish and Minimalism clearly inspired the aesthetic of many pieces in the show, such as Casa de Pancho Pantera and Ojos Azules, although the titles (and contexts within the exhibition) allude equally to issues of cultural slippage and police surveillance, respectively. The red, blue, and yellow stacked plastic boxes that make up NFPA: Pelayo López Curiel López Schneider López are part of a tradition that extends from the De Stijl Movement to Donald Judd, though in this case the use of primary colors also pulls from the color-coded system used by the National Fire Protection Agency to identify the molecular make-up of hazardous environments, invoked here by López as symbolic of his own (possibly combustible) familial and communal dynamics.

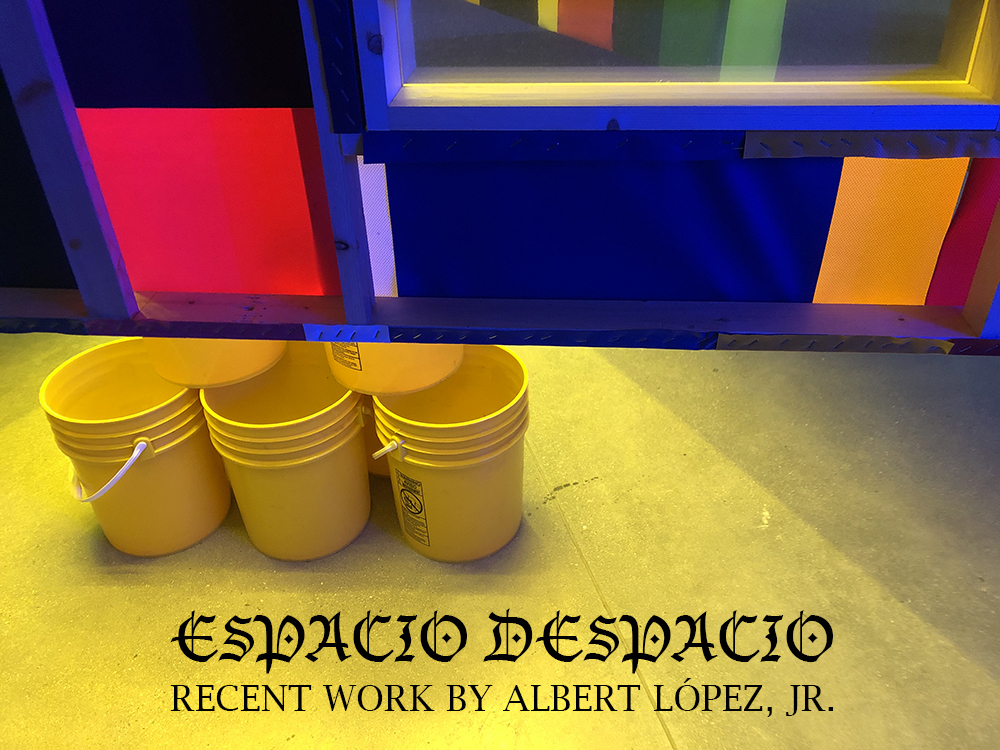

The center piece of the exhibition, literally and figuratively, The Lost Garden of Mondrian, remixes elements from a seminal work by the Argentine installation artist Leandro Erlich with the well-known rectilinear compositions favored by the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian, all made with López’s signature rasquache engineering. As in Erlich’s Lost Garden, López piece uses visual trickery to confound a simplistic perception of the relationship between interior and exterior space, further complicated by the aesthetic similarity between the pattern of woven PVC sheets that make up his structure and the Mondrian-inspired cladding on the exterior of the Cerritos College Fine Arts building. Even the slit-like one-way windows that provide a view into López’s installation are visually resonant with the clerestory windows piercing the exterior of the Fine Arts building, an unnerving coincidence considering the artist’s own carceral inspiration. In place of the lush garden at the center of Erlich’s piece, López’s installation is built around a stacked pyramid of empty yellow five-gallon buckets. Not unlike Andy Warhol’s Brillo Boxes, López invites the viewer to admire the simple beauty of these functional objects presented in a non-functional context. Illuminated by golden yellow florescent lights, the buckets, only ever partially in view, glow like precious relics on an altar, just as the light emanating outwards through the semi-transparent polyvinyl sheeting transforms the entire structure into something resembling a stained-glass window.

The religious symbolism of the garden as a site of origination and renewal - while not explicit in the work, absent, as it is, any actual plants - could be alluded to by the reused and appropriated buckets, sitting empty, ready to be put to their next task. This symbolic garden theme is perhaps more explicit, however, in the large LED-illuminated plexiglass installation in the gallery’s exterior window vitrine, into which is inscribed the word ‘COSECHA’ (Spanish for ‘harvest’). In an ideal world, this commanding text might be a call to, as Voltaire once suggested, “cultivate one’s own garden,” a metaphorical suggestion to cultivate your own aesthetic, to build your own universe, and share it with the people you love. But - and, in fact, sadly, more likely - the text could also be a warning that “you reap what you sow.” After all, the inverted pyramid of numbers hidden around the corner of the same installation were generated by counting and measuring the letters and spaces that make up the word at the other end, both ways of quantifiably ‘knowing’ the word without ever actually grasping its real meaning; not unlike, perhaps, a nosy police state seeking to weed and seed a community into oblivion, never truly understanding the value of the culture and, by extension, the people that live there.

ABOUT THE ARTIST:

Albert López, Jr. holds a BFA from California State University Long Beach and an MFA

from the University of California Irvine. He has exhibited widely, including at Crear

Studio, Wuho Gallery, Mesa Contemporary, Eastside International, D-Block, the MexiCali

Biennial, the East Gallery at Claremont Graduate University, Sol Art Gallery, MACO

International Art Fair, Miami Basel, Patricia Correia Gallery, and Edward Giardina

Contemporary. His work is included in the notable Cheech Marin collection. In addition

to his current solo exhibition at the Cerritos College Art Gallery, López has another

solo exhibition opening in April 2022 at S/A. Exhibitions in his native Santa Ana.

For more on Albert López Jr., see his website: http://www.albertlopezjr.com

Founded in 1955, Cerritos College is a public comprehensive community college in southeastern Los Angeles County. The mission of the Cerritos College Art Gallery is to serve as an educational, social, and cultural enhancement for the Cerritos academic population, as well as the immediate surrounding communities.

The Cerritos College Art Gallery presents rotating exhibitions highlighting the work of emerging and mid-career artists. A special emphasis is placed on works that confront challenging and pressing issues in contemporary art and culture. In support of exhibitions, the Cerritos College Art Gallery also regularly hosts workshops, lectures, and performances.

Admission and events are free and open to the public.

Daily Parking is available for $2.00 in lot C-10 in the student white stalls only.

Before entering any facility on campus, including the Cerritos College Art Gallery, all visitors are required to show proof of vaccination, including booster shots, at the college’s COVID kiosks. Visitors will not be allowed to enter the Cerritos College Art Gallery without a daily wristband from a COVID kiosk. Once inside the gallery, all visitors must wear an appropriate mask (surgical-grade or higher) and maintain proper social distancing. Please see https://www.cerritos.edu/covid-19/ for more information.

Daily Hours:

Mondays – Thursdays: 12PM-4PM

Nightly Hours:

Mondays & Tuesdays: 5PM-7PM

Weekend Hours:

Saturdays: 12PM-4PM

Please Note: The Cerritos College Art Gallery will be closed during the President’s Holiday (February 18 to February 21) and Spring Break (March 11 to March 20).

Stay Connected