Rio Hondo College Art Gallery SUR:biennial 2015

Exhibition Installation, Rio Hondo College Art Gallery, 2015.

THE PARADOX OF BELONGING

Inclusivity, Exclusivity, and Cultural Identity

Sheila Lynch

Rio Hondo College is a place in between. It is situated east of East LA, south of

South El Monte, north of North Orange County, and west of the city of Whittier. No

single culture defines it. Rather, it is the school’s plurality of heritages that

shapes it. Set on a hillside above the communities it serves, yet outside their city

limits, the school is as much a refuge from the nearby routine of city life as it

is a gathering place to explore ideas, challenge assumptions, and examine the past.

As James MacDevitt makes clear in “Comings and Goings,” his curatorial essay

for the 2013 catalog of the 2nd Los Angeles SUR:biennial, “SUR is not a race, an ethnicity, nor a people, rather, it’s a place, a region, a zone;

and, by extension, it’s an orientation as well, a directional focus. Los Angeles is

most definitely SUR. El Paso is SUR.”1 And, to paraphrase MacDevitt, Rio Hondo too.

Accordingly, the directional focus that characterizes SUR—this crossroads of migration,

expatriation, and exile—inherently points away from this very place, as well, toward

both near and far off lands. Woven into the very fabric of life in SUR is the complex

question of group identity. Belonging is multilayered. It is dependent upon personal,

social, and political constructs. Home is not a given. It is mutilvalent. In a culture

as migratory as Los Angeles, home is at once both “here” and “there” or, sometimes,

neither.2 And its meaning follows us, even into death. Through distancing humor, frank analysis,

and emotional attachment, a rich subtext emerges from these works to add to

our understanding of SUR.

The nine artists invited to exhibit at Rio Hondo College for the 3rd Los Angeles SUR:biennial

draw upon distant as well as recent history to meditate on the nature of personal

and social narratives, raising questions along

the way about community, displacement, and social justice. Taken as a whole with one

or two notable exceptions, the show’s installation serves as a searching lament over

past iniquities. Using irony, nostalgia, myth, comedy, or point-blank condemnation,

the works invite the viewer to take part in a first-person narrative journey. In an

art world that is frequently known to use cynicism as a calling card, the earnest

approach taken by these artists feels strikingly bold.

Five tombstones announce the show the way a civic monument defines a town square.

Lined up side by side on a carpet of sod grass, these grave markers form the centerpiece

of Ed Gomez’s installation Memorial while also taking center stage in the gallery.

The artwork is a simulation of cemetery plots, but the tombstones themselves are the

real thing. Gomez’s piece revives a local controversy over the sanctioned removal

of tombstones from two adjacent Whittier cemeteries in the 1960s when the city government

began executing plans to develop the land for public use. The bodies of over two thousand

people remain interred at the site of the old cemeteries. But the grave markers have

all been removed to make way for the city park that now obscures the land’s function

as a burial ground. Many markers were never claimed by family members and lie in piles

in a local museum’s storage yard where they have languished for years. All five of

the tombstones in Memorial once marked the gravesites of individuals born over a century

ago. When the installation is dismantled, these tombstones will be returned to their

storage yard. Gomez’s ironic title bears solemn witness to the slighted memory of

these individuals, exposing a present that privileges “land improvement” over promises

kept.

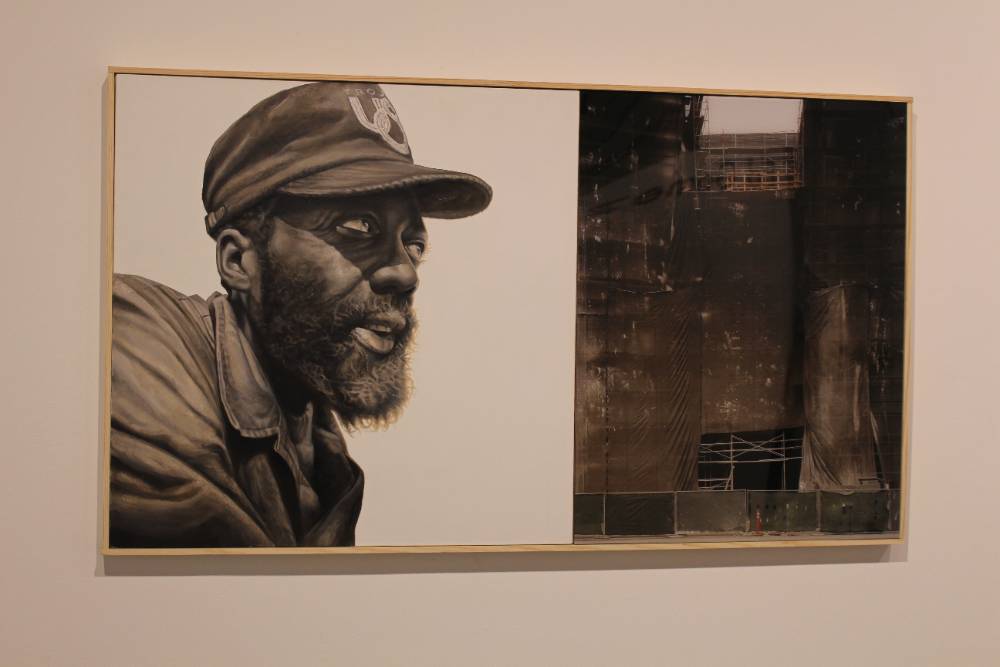

Redevelopment is addressed again in diptychs made collaboratively by Eloy Torres and

Julianne Backmann. Their works weigh the impact of the built environment upon social

interaction. Each work juxtaposes a photograph of a large building wrapped in black

construction mesh alongside a painted portrait placed within the same frame. The

word “expansion” begins the title of each work, while the rest of each title identifies

the Los Angeles location of the building under construction: Temple and Grand; Aliso

and Spring. As noted in their artists’ statement, their work focuses upon “the dichotomy

between corporate growth and individual poverty.” Through Torres’s ominous handling

of the subjects in his grisaille portraits and Backmann’s imposing treatment of the

looming buildings she captures with her camera, the works warn that the balance is

decidedly tipped in favor of corporate power.

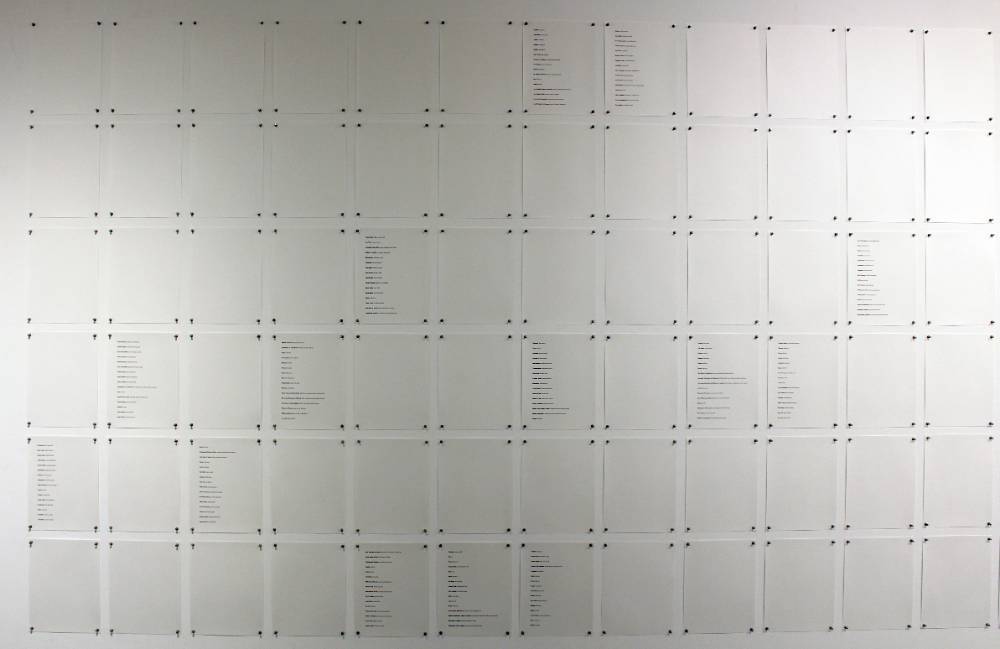

Shifting the locus of interest halfway around the world, Jimena Sarno’s untitled (how

to pronounce) covers the largest wall in the gallery with a tight grid of 240 sheets

of standard white copy paper. Most of the pages are left blank. Names are typed in

lists on 46 of the pages. As Sarno explains in a statement, these are the names of

people

killed in drone strikes in northwest Pakistan since 2004, while the blank pages stand

in for unknown casualties--the unidentified dead. After each name a phonetic pronunciation

of that name is given, presumably to help English speakers with the Urdu and Pashto

names that predominate the lists. This, of course, gives the artwork the “how to

pronounce” descriptor of its title, while alluding to the victims’ “foreignness” and

the ease with which they have become objectified. It also serves as a tacit indictment

of the United States government, whose armed drones are known to have targeted the

area throughout this same time period in efforts to quash terrorist groups. Sarno

cites The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, an award-winning non-profit organization

committed to educating the public “about the realities of power in today’s world,” as the source of her information.3 Her matter-offact presentation listing hundreds of victims’ names as mere data in

a routine report accentuates the cool detachment with which these lives were taken.

Technology becomes the great equalizer. Suffering the ultimate displacement, these

victims died at the hand of operators likely thousands of miles away who, with the

flick of the wrist, wiped out

their targets using remote control devices.

Traveling from Los Angeles to her childhood home by air would take Daniela Campins

an entire day, not counting layovers and being shuffled through various airports.

When she gets homesick, she doesn’t simply pack her

bags and hop on a plane. She has had to come up with other strategies. If her two

works on paper in this show are about place, that place might be Venezuela, where

Campins lived from the age of two until moving to the United States as a young adult.

The paintings’ titles recall the music of Sentimiento Muerto, an influential post-punk

band out of Caracas which is thought by many to be the most important Venezuelan rock

group of all time. Both of her works in the show take their names from the band’s

songs. The painting Un Agradable Calor uses that song’s title as

its literal subject matter, repeating its three words across the page again and again

upon the uppermost layer of the painting’s surface. Orienting the finished work so

that the words are seen upside down subverts the reference

to the band and draws attention, instead, to the gestural quality of the artist’s

hand. Less an exercise in Surrealist automatism than a celebration of the materiality

of her paint, for Campins, mark making is an end in itself. The works exude a sense

of spontaneity and delight in her studio practice, rather than a forlorn sentimental

tone. Campins claims her grounding in the very act of painting, itself.

Delirious chaos swarms across the surfaces of Gerardo Monterrubio’s porcelain works.

With frenzied figural images and a stifling compression of space, each piece lays

bare the Dionysian underbelly of urban life. Scenes of sex, drinking, gambling, street

fights, incest, a charging bull, a marching band, attack dogs, a wrecking ball, and

a torrent of brutality cascade upon one another on objects made of porcelain, the

fine substance once used exclusively for luxury items only royalty and aristocrats

could afford. Skeletons and menacing clowns dance and leer across

the lumpy contours of Monterrubio’s ceramic sculptures. Combining the idiom of prison

tattoos with that of street art, and the horror vacui of ancient vase decoration with

the mural-painting styles of David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco, Monterrubio’s

disjointed narratives deliver a dizzying punch. He approaches his subjects as an amateur

anthropologist might, intent on recording the customs of the particular culture he

is studying. For Monterrubio, that culture consistently remains the contemporary street

life of SUR.

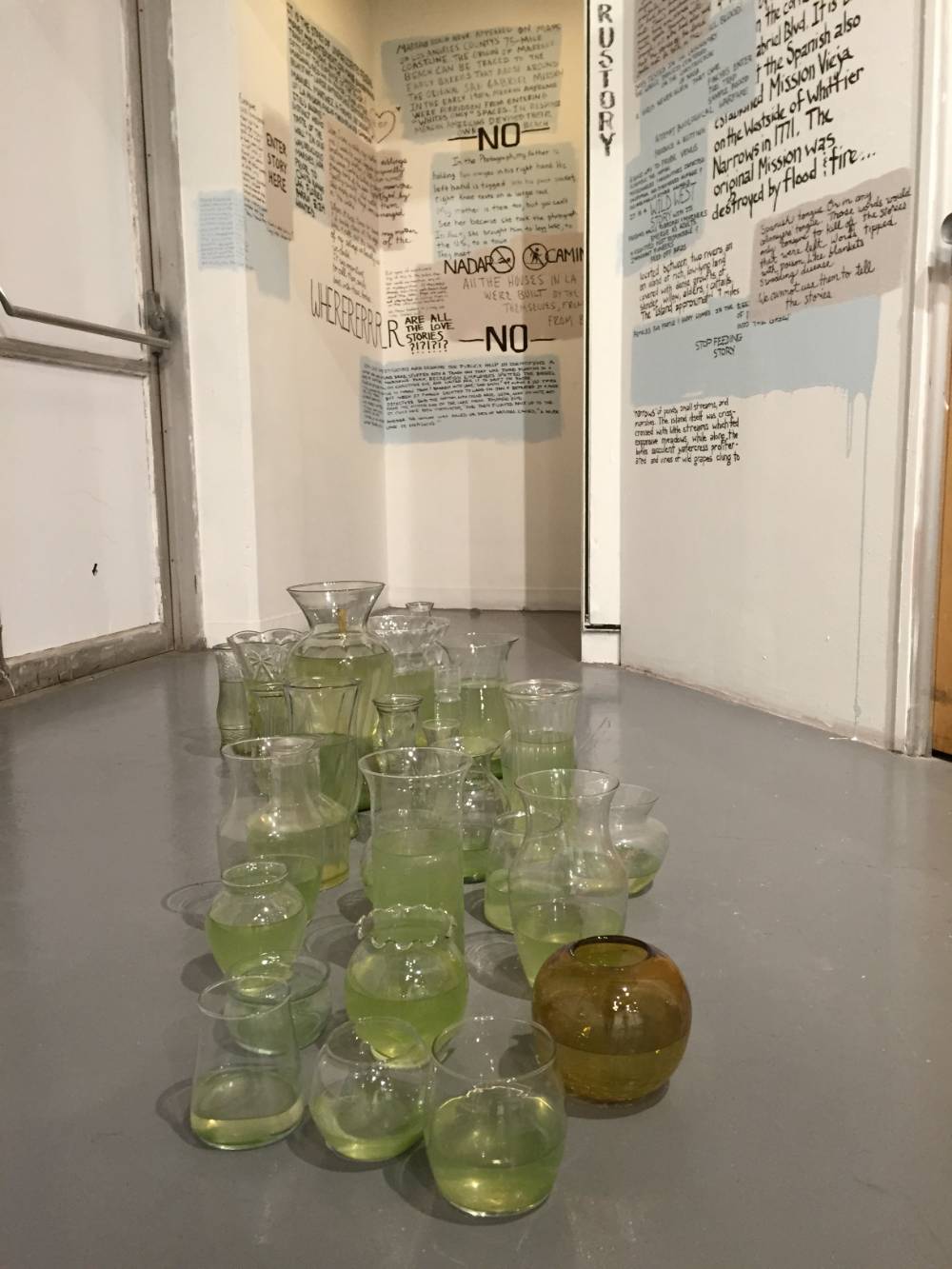

Submerging themselves in the past, Carribean Fragoza and Romeo Guzmán’s collaboration

Suburbiaquatica is a plaintive homage to a history that is almost within reach. Fragoza

and Guzman’s site-specific installation

floods an alcove of the gallery in layers of handwritten wall text, each one eclipsing

the former the way fragmented memories might. Passages read like stories recounted

at family gatherings or faded newspaper clippings found in a scrap book. They tell

of drugs, displacement, disease, discrimination, drowning, and a lynching: events—some

factual, some mythical--associated with specific local bodies of water. Sitting on

the floor in front of the graffitied alcove are more than two dozen glass jugs filled

with water from nearby Legg Lake. As it happens, a grand view can be had a few steps

outside the art gallery doors of the watershed of two rivers: the San Gabriel River

and Rio Hondo, the river that gives the college its name. Between these two rivers

sits Legg Lake. Just a short walk from the lake is the original site of the San Gabriel

Mission alluded to in Fragoza and Guzmán’s wall text, La Misión Vieja.4 This site, known historically as Isanthcogna, was home to the Gabrieleño-Tongva people,

the first inhabitants of this region, before they were forced by missionaries to relocate.5 Suburbiaquatica subtly brings this complex social history of the land between the

rivers onto the hill that overlooks it and then into the gallery, along with samples

of its eerily green water. More poignantly, Fragoza and Guzman’s installation expresses

the longing for a shared past in a region where that past is often erased before the

collective will recognizes the need to preserve it.

Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia presents a deft view of flawed cultural syncretism in his

artwork Hemos jurado amarnos hasta la muerte y si los muertos aman, después de muertos

amarnos mas. He paints a picture of a domestic setting in which Mexican folk traditions

and Euro-American styles come together but only by proximity. The two cultures share

the space like strangers in an elevator, having no relationship with one another and

nothing to exchange. In his painting, Hurtado Segovia depicts brightly colored papel

picado banners—whose chili peppers and bowls are arranged to resemble scowling faces—strewn

across the space before a wall decorated with orderly French Imperial fleurs-de-lis.

An Eames lounge chair, that icon of Modernism, sits in the foreground with its matching

ottoman while a decorated shamanic staff stands erect behind it. For further contrast,

Hurtado Segovia mixes pictorial conventions in this work by superimposing both flattened

and illusionistic space. Even the painting styles don’t harmonize. Hemos Jurado presents

a clash of cultures that are merely coexisting under the same roof.

It’s worth noting that Hurtado Segovia was born and raised in Ciudad Juárez, situated

across the Rio Grande from El Paso, Texas and one of Mexico’s largest border towns.6 Since the passing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1993, the

population of Ciudad Juárez has more than doubled.7 The city’s increased violent-crime rate since NAFTA was enacted has been a topic of

international headline news for more than two decades. Fear and economic decline grip

the city. The hope that free trade with the North would improve the lives of the

working class in Mexico has disintegrated. Transnational corporations have been the

greatest beneficiaries of NAFTA, while the working class has paid the steepest price.

Of the seventeen largest factories in Ciudad Juárez, only two are Mexican-owned. Nearly

half are owned by U.S. corporations.8 Globalization has created what Noam Chomsky

calls “islands of enormous privilege in a sea of misery and despair.”9 The long title of Hurtado Segovia’s painting refers to a vow, un juramento. Although

the title is a line from a love song, it brings to mind the vows made

by the architects and politicos of NAFTA and the great responsibility that comes with

the power to include and exclude.

On an intrapersonal level, belonging can be defined as a sense of feeling “at home” in a place. On an interpersonal level, belonging is a process that is negotiated through the politics of creating, justifying, or resisting social inclusion and exclusion. By turns, each artwork in Rio Hondo’s exhibition for the 3rd SUR:biennial addresses the latter concept. “Every politics of belonging involvestwo opposite sides: the side which claimsbelonging and the side which has the powerof ‘granting’ belonging.” From the decisions made by global power structures, corporate policymakers, and city governments all the way to the consequences of street fights, personal home-decorating choices, and a preference for nostalgic music, the stories told in each of these absorbing artworks remind us of the longing that is at the core of be-longing.10

END NOTES

1 James MacDevitt, “Comings and Goings,” 2nd Los Angeles SUR:biennial (Cerritos: Cerritos College Art

Gallery, 2013), 27.

2 For a discussion of art and migratory culture in Los Angeles and elsewhere, see

Mieke Bal and Miguel Á.

Hernández-Navarro, Art and Visibility in Migratory Culture: Conflict, Resistance,

and Agency (Netherlands: Rodopi, 2011).

3 “About the Bureau - The Bureau of Investigative Journalism” The Bureau of Investigative

Journalism,

n.d. Web. 17 November 2015 <https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/who>

4 “Attachment C: Historical Resources Evaluation Report for the State Route 710 North

Study,” California

Department of Transportation, (December 2014), 18. Web. 17 November 2015 https://libraryarchives.metro.net/DPGTL/eirs/sr-710-north-study/2014-sr-710-north-study-historic-property-survey-report-attachment-c-1.pdf

5 “Bosque del Rio – Parks | L.A. Mountains.com,” L.A. Mountains.com (Santa Monica Mountains

Conservancy: 2015) Web. 17 November 2015 < http://www.lamountains.com/parks.asp?parkid=3>

6 “A Conversation with Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia,”Cloth Paper Scissors (CB1 Gallery: 2015) Web. 7

December 2015 <http://cb1gallery.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/lorenzo-hurtado-segovia-clothpaper-scissors.pdf>

7 Regional Stakeholders Committee, “The Paso del Norte Region, US-Mexico: Self-Evaluation Report”, OECD Reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development, IMHE, (The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: 2009) 2, Table 1.1. Web. 7 December 2015 <http://www.oecd.org/edu/imhe/regionaldevelopment>

8 David Bacon, “The Maquiladora Workers of Juárez Find Their Voice,” The Nation (The Nation: 20 November 2015), Web. 7 December 2015 <http://www.thenation.com/article/the-maquiladora-workersof-juarez-find-their-voice>

9 Noam Chomsky, “Notes on NAFTA: The ‘Masters of Man,’” Chomsky.info (The Nation: March 1993)

Web. 7 December 2015 <https://chomsky.info/199303>

10 Marco Antonsich, “In Search of Belonging: An Analytical Framework,” Geography Compass (Vol 4, Issue 6, 1 June 2010), 645, 650, 652.

Daniela Campins, Unaradable Calor, Acrylic on Canvas, and, Sin Sombra No Hay Luz,

Acrylic on Canvas, each 22.5" x 15", 2015.

Daniela Campins

Daniela Campins was born in Leeds (England) and grew up in Venezuela. She lives and works in Los Angeles, California. She completed her MFA at the University of California Santa Barbara, and her BFA from California State University Long Beach. Campins was a recipient of the Painting and Printmaking Fountainhead Arts Fellowship from Virginia Commonwealth University. She has exhibited in Los Angeles (CA), San Francisco (CA), New London (CT), Richmond (VA), Tokio (Japan), and Kustavi (Finland). Daniela belongs to Manual History Machines, an LA-based curatorial collective invested in creating visibility for emerging and/or often overlooked artists who work in a variety of media from Los Angeles and beyond.

Carribean Fragoza & Romeo Guzman, Installation (Suburbiaquatica), Mixed Media, Demensions

Variable, 2015.

Carribean Fragoza & Romeo Guzman

South El Monte Arts Posse (SEMAP) is a collective of artists, writers, urban planners,

educators, scholars, farmers,

ecologists, swap meet vendors, and youth dedicated to engaging with the South El Monte

and El Monte community

through the arts by rethinking our use of space and transforming how we inhabit it.

Unlike most arts organization,

we do not house SEMAP operations and projects in a building. This is an integral part

of our community-building process as it ensures that all our projects are site-specific

works of public art. When we exhibit in gallery spaces, we make sure to translate

the public and often process-based nature of the projects for gallery audiences, often

integrating interactive and participatory elements. SEMAP believes that the nature

and function of space is constructed by the imaginings of the people who take it upon

themselves to shape it. Our mission is to shift the relationship between the bodies

of SEM/EM residents and transients and the physical spaces they inhabit by using art

to foster agency, ownership, and grassroots democracy. We seek to create a sense of

ownership of community not based on proprietorship over buildings or land, but based

on residents’ connection to place through personal and communal narratives. By building

community across varied and diverse groups and interests in SEM/EM we seek to find

points of intersection. In doing so, we create opportunities for people of all ages

and backgrounds to

imagine possibilities for positive change in their community. Through the arts, SEMAP

strives to democratize access to both art practices and place making.

Carribean Fragoza and Romeo Guzman co-direct the South El Monte Arts Posse. Fragoza is an interdisciplinary writer and visual artist living and working in Los Angeles and in her hometown, South El Monte. She is a graduate of UCLA and CalArts’ MFA Writing Program. She is currently working on several book projects. Guzmán grew up in Pomona, spending many summers and weekends con los tios/tias in South El Monte. He received his BA at UCLA and is currently completing doctoral studies at Columbia University.

Ed Gomez, Founder's Memorial, Found Tombstones, Grass, and Burial Documentation Materials,

Dimensions Variable, 2015. Installation shot of Tombstones.

Ed Gomez

Founders Memorial is a temporary memorial honoring some of the earliest residents of Whittier, California. It is a direct reference to Founder’s Memorial Park, a green space which has replaced the previous land occupied by two adjacent burial grounds, historically known as Mount Olive and Broadway Cemeteries. Due to these plots becoming abandoned and run down, the City of Whittier decided it was in the city’s best interest to turn these graveyards into a community park. In the mid to late 60s, attempts to locate family of the interred were initiated. All headstones were cleared, many of which were offered to known family members. Several family members were unlocatable or unwilling to take the headstones. As a result, the tombstones have been displaced for decades. Temporarily, these headstones were relocated to the Rio Hondo Art Gallery as part of the SUR:biennial.

Ed Gomez is an artist, educator, and curator who received his BFA from Arizona State University in 1999 and his MFA from Otis College of Art and Design in 2003. His interdisciplinary art practice revolves around the questioning of exhibition practices, institutional framework and historical models of artistic production. In 2006, he co-founded the MexiCali Biennial, a bi-national art and music program addressing the area of Mexico and California as a region of aesthetic production. He is currently a director and co-president of this non-profit arts organization. Mr. Gomez is also the director of G.O.C.A., The Gallery of Contemporary Art, which is a traveling self-contained exhibition space humorously located in his suitcase. It has showcased emerging and established artists from Los Angeles, Phoenix, New York and Mexico.

Gerardo Monterrubio, Untitled, Ceramic, 29" x 18" x 16", 2015.

Gerardo Monterrubio

A ceramic artist, Gerardo Monterrubio was inspired by the narratives drawn onto the

clay pots of early South American native cultures and has taken it upon himself to

create a historically based narrative of his own present day culture. Using symbols

of Latino street culture he carefully draws emotionally derived scenes common of life

on the streets in Los Angeles. In this way, he documents the common struggles and

issues of modern urban society. As Monterrubio states, for many millennia, numerous

cultures have used the ceramic medium to record their existence. From these artifacts,

we can form an understanding and various interpretations of the cultural paradigms,

socio political practices, mythologies, and the human experience of the worlds that

created them.It is

this anthropological aspect that propels my work in its creative endeavor, using the

forms as vehicles to compose linear and fragmented narratives. Altered by the imagination,

memory, and the like, my work engages the idea of recording selected aspects of contemporary

society, in methods that are as old and universal as human creativity itself.

Born in Oaxaca, Mexico, but LA-based since the age of ten, ceramicist Gerardo Monterrubio received his Bachelor of Fine Arts from Cal State Long Beach and his Master of Fine Arts degree at UCLA. Monterrubio participated in a 2010 artist residency in Guandong, China and his solo exhibitions include Fused (Ferris Gallery, Pittsfield, MA) and Clay Street (Armstrong Gallery, Pomona, CA). His work has also appeared in group exhibitions, such as Exposed (American Museum of Ceramic Art, Pomona), Re-Objectification (Ferrin Gallery, NY), and at the CSULB University Art Museum and the California Conference for the Advancement of Ceramic Arts. Monterrubio teaches ceramics at Long Beach City College.

Jimena Sarno, Untitled (How to Pronounce) Text on Paper, 2015.

Jimena Sarno

Jimena Sarno is a multidisciplinary artist and organizer. She was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina and currently lives and works in Los Angeles, CA. She works across a range of media including installation, sound, video, text and sculpture. She is the organizer of analog dissident, a monthly discussion gathering that encourages intersectional approaches, aimed at queer/radical/immigrant artists and thinkers to engage critically outside of traditional art institutions and social media.

Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia, Hemos Jurado Amarnos Hasta La Muerte y Si Los Muertos Aman,

Despues De Muertos Amarnos, Acrylic on Linen, 92" x 107", 2015.

Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

Born in Cd. Júarez, Chihuahua, Mexico, Hurtado Segovia graduated with a BA from UCLA in 2003 and an MFA from Otis College of Art and Design in 2007. The Vincent Price Art Museum organized his first solo exhibition, a survey of work from 2007 to 2014, Mis Papeles in 2015. Additionally his work has been featured at the Craft and Folk Art Museum, the LA Municipal Art Gallery and in the SUR Biennial. His work is in the collection of The Hammer Museum and Murals of La Jolla, as well as several corporate and private collections. He lives with his wife and two children in Los Angeles where he also maintains his studio. Hurtado Segovia is Associate Professor at Otis College of Art and Design.

Eloy Torrez & Juiane Backmann, Espansion - La Brea and Wilshite, Oil on canvas & LAMBDA

Print, 30" x 60", 2015.

Eloy Torrez & Juiane Backmann

In the case of both Torrez and Backmann, the work isn’t about what unfolds in front

of the viewer. It’s about the cracks in between. It is work that tells of the passing

of time–not of people and not of places. Generations unfold in Torrez’s surreal scenes–that

which brings his subjects together is seemingly

less powerful than the stories that divide them. In Backmann’s photographs, time of

day is obscured and purpose of space is obscured too. Hers are still lives of a place

caught off-guard and off-duty. Combined, the works of these two artists is a convergence

of oblique narratives and stories partially told. Backmann claims that she has been

intrigued by areas of Los Angeles that, without purpose, look like movie sets right

after the crew has left. Photographed as scenic canvases they invite the viewer to

imagine characters and a plot.

Eloy Torrez is a painter, artist, muralist, and art instructor. Born in Albuquerque, New Mexico, he lives and works in Los Angeles. He has a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from Otis College of Art and Design. He is known for his photorealist/surrealist style. Torrez has executed murals in the Southern California area, including the well-known The Pope of Broadway, or the Anthony Quinn mural, at the Victor Clothing Co. buildings in downtown Los Angeles at 240 S. Broadway. He has also painted murals in St. Denis, France, as an artist in residence. His oil paintings and works on paper have been exhibited in galleries and museums in the United States, Mexico, and Europe. Torrez teaches drawing to youths at risk at the Covenant House in Hollywood, California, as well as art and mural painting to children, youth, and adults. He also composes pop music, sings, and plays guitar.

Born in Muenster, Germany, Juliane Backmann studied photography at the Academy of

Photo design in Munich and

after graduating worked in Hamburg and Munich. In 1991 she came to Los Angeles where

she now spends most of

the year working on numerous fine art projects that include documenting urban landscapes

as well as a number of

portrait series, utilizing different photographic approaches, like assemblage and

collage as well as unconventional

darkroom techniques. Her photographs, collages and installations have been exhibited

throughout California and Germany. After doing still photography for more than twenty

years she has recently started working with video and moving images.

Stay Connected