Cerritos College SUR:biennial 2013

SUR:Biennial > 2013 > Cerritos

Daino, To Whom It May Concern, 2013.

Comings And Goings

Alien Phenomenologies, Precarious Memories, And Transient Exchanges

By James Macdevitt

On October 25th, just one day after the 2nd Los Angeles SUR:biennial opened to the public, the Washington Post’s art critic Philip Kennicott published a review of the Smithsonian Museum’s Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art, a contemporaneous survey of work by Latin American artists living in the United States. The review itself was far from complimentary on a number of levels, but its primary critique centered on what the critic seemed to (mis-)perceive as the current limits of identity-based exhibitions (or, at least, as they apply to minoritarian communities), which he summarized by labeling the exhibition “a telling symptom of an insoluble problem: Latino art, today, is a meaningless category.”1 Expanding on this interpretation in a later dialogue with artist/filmmaker Alex Rivera, necessitated by the almost instantaneous backlash to the review on social media sites, the critic went on to ponder whether “all of the art [by artists of Cuban, Puerto Rican and Mexican heritage] [is] in fact linked by some essential unifying thing? Is the art made by a Cuban exile educated in Paris somehow similar to street art made by a Mexican American in Los Angeles?"2 Ironically, and in some opposition to his demand for survey exhibitions with greater degrees of granularity, the very same day that Kennicott published his review, it was announced that famed performance artist Adrian Piper had pulled her work from the exhibition Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery, citing the need to “curate multi-ethnic exhibitions that give American audiences the rare opportunity to measure directly the groundbreaking achievements of African-American artists against those of their peers in ‘the art world at large.’”3

On a superficial level, these two public rejections, by both a well-known critic and a celebrated artist, seem to suggest hard times ahead for identity-based curation. But the dueling critiques of curatorial breadth (Kennicott) and ghettoization (Piper), suffer from the same basic, and fallacious, assumption: that membership in any particular identity-grouping (Latino, Cuban, Mexican-American, Black, etc.), whether it be self-actualized or collectively imposed, is a fixed characteristic that is either present or absent, that one either has it or does not. In his nuanced rebuttal to Kennicott’s position, Rivera makes an alternative case for flexible and fluid demarcations in the category of ‘Latino/a artist,’ while simultaneously validating the need to recognize the existence of such a category in the first place. “In terms of what unites Latino artists, well, it might be aesthetics that one way or another trace back to distant Spanish and Indigenous influence. It might be an engagement with questions of assimilation in the U.S. or of migration or exile. It could be none of these. But one strong glue that unites the community of Latino artists I know is awareness that we’re still ‘outsiders’ in spaces which claim to speak for the nation.”4

This debate between Kennicott and Rivera (and the constituencies that they represent) is not likely to be resolved any time soon, but it does highlight one perpetual truism; that the boundaries of any class(ification) system are always already political, and are, therefore, contestable. Rather than trying to simply historicize, essentialize, or standardize a definition of Latino/a identity against which a participating artist might be weighed and measured, the SUR:biennial operates on a principle of expanded categorization, though doing so with full recognition of the contextual nature of these kinds of coalitions and without seeking to erase difference(s) entirely. It is with this in mind that the SUR:biennial strives to move away from the now commonplace rhetorical strategies of contemporary exhibition whereby, as Rasheed Araeen, the founder of the influential postcolonial journal Third Text, explains, while “the white/European artist has no obligation to the multicultural society and he does not require any identity sign for the work to be recognized; the ‘other’ artists must carry the burden of the culture from which they have originated, and they must indicate this in their artworks before they can be recognized and legitimated. Their works must carry identity cards.”5 This is, of course, exactly Rivera’s critique of the inverted assumptions in Kennicott’s previously mentioned review, as he makes clear when he pointedly asks the critic “I understand your observation that there’s a lot of diversity within the imagined community of ‘Latinos.’ But what big grouping of people doesn’t embody diversity and conflict within itself? I imagine you regularly review shows in museums of ‘American Art,’ but never spend the review space critiquing the concept of ‘American’ (which is more broad than the category ‘Latino’). Why attack categories like ‘Latino’ when they’re used pro-actively to organize a show, while other vague categories are left unquestioned?”

This is, in part, why, from its very inception, the SUR:biennial took a different approach and quietly sidestepped the, by-now decades-old, ‘Latino/post-Latino’ debate (however valid and necessary that discussion might be). Artists were not included nor excluded based on their individual identity alone, but neither were those identities ignored. After all, as the name implies, SUR, which translates to ‘south’ in Spanish, is not a traditional taxonomic term for an ethnicity or nationality. SUR is not something one person has; it is not an attribute to be gained or lost. SUR is not an either/or proposition; it is a spectrum, and a dynamic and intersected one at that. SUR is something within which one participates. SUR is an enfolding, an entanglement, an ecology. And yes, SUR is Latino too. It can’t help itself; it does so without even trying. Don’t get confused here; SUR is not a race, an ethnicity, nor a people, rather, it’s a place, a region, a zone; and, by extension, it’s an orientation as well, a directional focus. Los Angeles is most definitely SUR. El Paso is SUR. Miami too. And they are not alone.

At the same time that he denounces the systemic hypocrisy of the global art markets, and following Franz Fanon’s critique of the collective psychosis of colonized and colonizer alike in French-occupied Algeria, Araeen posits the need to recognize that, in a globalized world, “we are all postcolonial subjects, irrespective of racial differences and cultural backgrounds, and it’s only on this basis that we can have a dialogue and discuss the issues together which concern all of us.”6 As an ardent and vociferous advocate against Euro/Anglo-centricism, Araeen is clearly not suggesting here that difference be, as the saying goes, ‘white-washed,’ but rather is attempting to provide a more productive alternative paradigm for discussing and, ultimately, combating the inequalities resultant from it. One might look at it this way: in Los Angeles (and El Paso and Miami, etc.), everyone and everything is (becoming) SUR,7 in the same way that peninsulares and criollos and mestizos and indios were all (becoming) Mexican through their (inter)actions in the 18th-century Viceroyalty of Nueva España.

W.J.T. Mitchell in his recent essay “World Pictures: Globalization and Visual Culture” discussed the growing importance of the geographic assemblage of the ‘region’ despite, or perhaps because of, the influence of globalization. “Regional imaginaries”, as he calls them, “always display a double, dialectical face. The region is what is ‘ruled’ [regere, ‘to rule’], but it is also what is free of central rule, contesting the power centers … the region is a much more tentative and provisional entity than a nation or country.”8 It is in the spirit of this regional and orientational conception of the SUR:biennial, especially in its distinctive elusivity, that this year’s curatorial theme at the Cerritos College Art Gallery was chosen to be “Comings and Goings: Alien Phenomenologies, Precarious Memories, and Transient Exchanges.” Territoriality, after all, inevitably implies motion and any movement is, by definition, bi-(and even multi-)directional; any arrival is also a departure, and vice versa.

Without a doubt, the US/Mexican border plays a part in this, but not exclusively so and certainly not in the way it is all too frequently conceived in discussions of Latin American cultural in the United States. Andres Payan, for example, in his tripartite contribution to the exhibition, explores the mundane phenomenon of living bi-nationally, crossing the border not as a mythical voyage to political freedom or economic opportunity, but simply as a matter of everyday practice, of rote existence. Born and raised in Juarez, Payan crossed the border daily to go to school in the US. In his project titled Spatial Imaginary, he juxtaposes two digital printouts of satellite photos of his homes in both Juarez and El Paso, complete with physical map pins to symbolically represent their geo-spatial positions, in the now all-to-familiar interfacial formula of Google Maps. Placed one above the other, the two framed prints create an artificial border between them, while the alignment of a vertical road seems to cut across both imaged cartographies, joining the two disparate locals in the viewers’ mind, while highlighting, in their juxtaposition, the disjunctions in urban density extent between both locations.

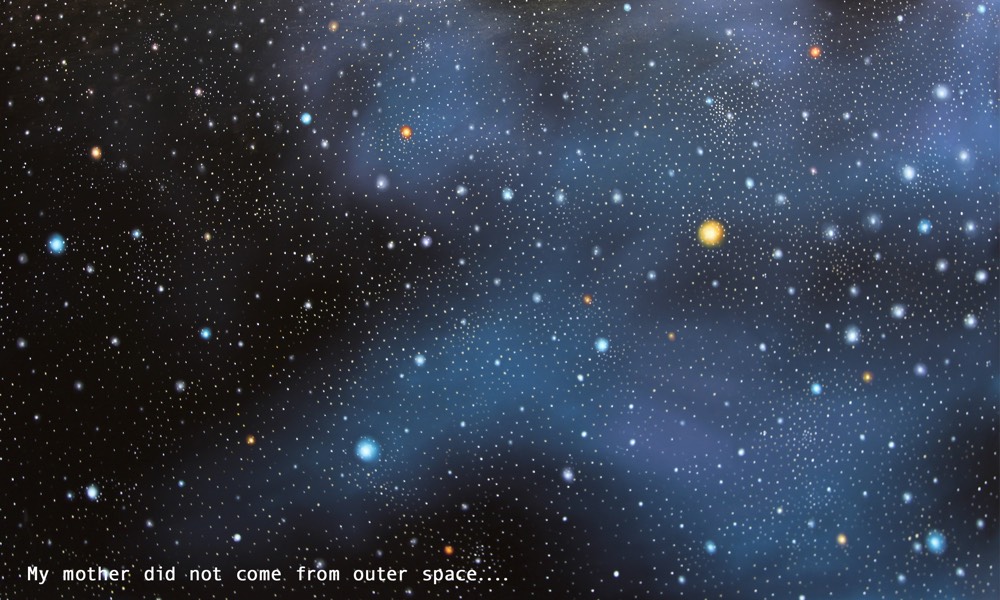

It should be noted here that the choice of satellite imagery also underscores the way that hyper-modern technologies are integral these days to maintaining the illusory distinctions between ‘here’ and ‘there,’ and establishing a sense of otherness, not only as an abstraction, but also as a mode of lived experience manifested by, and through, that construct. It’s not by accident that Payan’s Googled border map is hung in the gallery next to Nery Gabriel Lemus My Mother Did Not Come From Outer Space, whose textual component plays off the common linguistic parlance in the US for nationalized Otherness (i.e. alien), while depicting the vast emptiness of vacuous space (an ironically inverted gaze away from the blue marble of earth, which had once held such imagined promise as a symbol of global unification and peace when it was first released by NASA in 1972).9 What grandiose rhetorical terms like ‘alien’ tend to rationalize, alluded to by both the macro- and micro-perspectives in Lemus and Payan’s pieces respectively, is not just the Wagnerian-level tragedies resultant from harsh immigration policies against undocumented migrants, but also the invisible micro-brutalities that are built into a system that regulates everyday legal movement across any politically-sanctioned border.

Payan’s Ex-Change brings those accumulative injustices further to light by documenting the routine of his own daily border crossings through the currency exchange receipts generated by those very movements. In just twenty-two separate crossings, his initial ten-peso bill was reduced to half its market value through incidental fees and adjusting exchange rates. The artist’s Mexican-ness is not marked here through reductive and stereotypical imagery, but rather by the bureaucratic detritus of life in a globalized, interconnected society. In other words, the artist defines his Mexican/Latino identity, at least in part, as the outcome of embodied interactions with international (and yet fully institutionalized) power structures; not as a static cultural archetype, but as a relative positionality within a matrix of geo-political-economic systems of hegemony. However, unlike Gulsun Karamustafa’s slightly older currency-based project, Objects of Desire / A Suitcase Trade (100 Dollar Limit) made for the MoneyNations exhibition at the Shedhalle in Zurich in 1998, which referenced the so-called suitcase trade, an illegal trans-border economy existing between Turkey and the former Soviet republics, Payan’s Ex-Change project chooses to subvert the regulating power of institutional systems by presenting the actual physical documents of that regulation, rather than enacting, as did Karamustafa, a guerilla-style attempt at evading that regulatory gaze.

However, complimenting Payan’s other two exhibited projects at Cerritos is just such a subversive piece, Geophagy, presented as a more traditional performative document, a video recording, in this case of the artist eating what appears to be, at first glance, a chocolate cake, but which, on further inspection, comes to be understood as a cake-shaped formation of dirt from the artist’s hometown of Juarez, smuggled across the border into El Paso, where it was prepared and, ultimately, consumed. Referencing notions of childhood nostalgia (it’s a literal mud-pie), as well as developmental disorders (pica is the desire to devour non-nutritional substances like dirt), Payan’s consumption is painful to watch in its nauseating viscerality, but also conceptually disconcerting in the way it replicates post-NAFTA production and consumption dynamics between the US and Mexico (think maquiladoras along the border) and in its flaunting of the traditional categories of artist and material (Payan is a ceramicist by training, so he frequently ‘works’ with the earth by other means).

While Payan’s pseudo-triptych examines (in)dividuated subjectivities directly at the physical border, other projects featured in the exhibition at Cerritos highlight the fact that crossing borders doesn’t necessarily mean moving bodily across a terrestrial hetereotopic boundary. Ignacio Perez Meruane’s DHS Envelopes Installation, for example, traces the artist’s multi-year naturalization process following his marriage and immigration from South America. In Perez Meruane’s case, the literal border, as a physical space between the US and Mexico, had nothing to do with his own nomadic experience. Instead, his crossing was one of airports, with clouds in-between, followed by correspondences with anonymous governmental agents. But, like Payan’s experience documented through his currency receipts, the form(al) exchanges between Perez Meruane and the Department of Homeland Security still functioned as a micro-process of subjectification. As Louis Althusser posited in his 1970 essay Ideology and the Ideological State Apparatuses the subject is constructed through acts of ideological interpellation, a hailing that is akin to a police officer shouting ‘Hey, you there’ and the transformation that occurs when you respond to that hail by turning around, simultaneously acknowledging, with that act, the authority of the state apparatus and your own submission, or rather subjection, to it. Althusser’s “mere one-hundred-and-eighty-degree physical conversion,”10 in Perez Meruane’s case from foreigner (a member of an-Other nation-state) to Latino (an marked census category linked to recognition of citizenship by the adoptive nation-state) is alluded to through the chronological placement of individually-framed, bisected envelopes received from the DHS.

Filleted and displayed, inside-out as it were, these decorative anthropological specimens are set against a backdrop of wallpaper formally inspired by the privacy-screen pattern visible on one of the envelopes. The domesticity referenced by the atypical wallpapering of the gallery, a practice normally reserved for the personalized space of home interiors, further complicates the supposed division between public and private spaces that is also referenced by the exposed innards of the envelopes themselves. Like the artist’s (or any) marriage, the process of naturalization, of becoming (an) American, is not just a personal journey of private identification, but also a public spectacle (if only for the insatiable scopophilic impulses of governmental institutions, via bureaucratic officials and/or, increasingly, algorithmic datamining). However, in isolating the envelopes from the officiating forms within, and the individuating information they ostensibly contain, Perez Meruane himself transforms the mundane objects of the ideological state apparatus into objects of aesthetic contemplation (nearly) devoid of their institutional specificity (and, by extension, their agency and authority).

Rather than trying to re-present the system of naturalization, the installation intentionally fails to fully represent the objects (and attendant subjects) of said system, playfully posing a dialogic reciprocity with apparatuses of the state that curtails some, though certainly not all, of Althusser’s more hyperbolic fears about authorial address (note the overt blankness in the area of each windowed envelope that would normally reveal the delivery address of the recipient). In effect, Perez Meruane’s installation posits the Althusserian turn-around-towards as a simultaneous turn-away-from, such that “we might conceive of the entry into the symbolic order as less terminal, not determined by such delimited notions of temporality [as before and after]” subjectification.11 Rather it’s an ongoing, and therefore perpetually negotiated, process; a co-respond-dance.

Likewise, Gala Porras-Kim’s contribution to the exhibition presents a playful (and, in her case, interactive) pastiche of the agency-erasing conception of ideologically-institutionalized subject-formation. In a series of diptychs, Porras-Kim replicates, in graphite, images of various ancient stelae carrying inscriptions of linguistic signification. Excised from the completed drawing displayed within one frame, the symbols are removed from their relative contexts and (dis-)placed into the adjacent frame following artist-imposed logistics of arrangement, such as size and shape. The viewer, confronted by an “ironic enactment of a linguistic causa sui,”12 is placed in the empowered, and yet paradoxically disoriented, role of archeo-linguist, attempting to (re-)orient these Derridean archi-writings, to reconstruct the (meanings of the) past in the present. In an inversion of Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document,13 which traces her newborn son’s gradual induction into the shared realm of symbolic language, Porras-Kim’s pseudo-crypto-documents remove the viewer from those meaningful structures of commun-ication, isolating them outside the circuit of the symbolic-real-imaginary order. Rather than presenting the discipline of linguistics, and, by extension, language itself, as an “exact science,” which Lacan would define as the “the field of phenomena in which there is no one who uses a signifier,”14 any linguistic abstraction is instead understood here as the product of a “conjectural science;” i.e. specific, embodied, politicized (not just ideological), and, ultimately, non-sensical. As Gilles Deleuze pointed out, however, “non-sense is not at all absurd or the opposite of sense, but rather that which gives value to sense and produces it by circulating in the structure.”15 Again, as with Perez Meruane’s installation, it is the ongoing circulation of meaning that replaces, in Porras-Kim’s project, the ‘before’ and ‘after’ interpellation of the individual/subject divide.

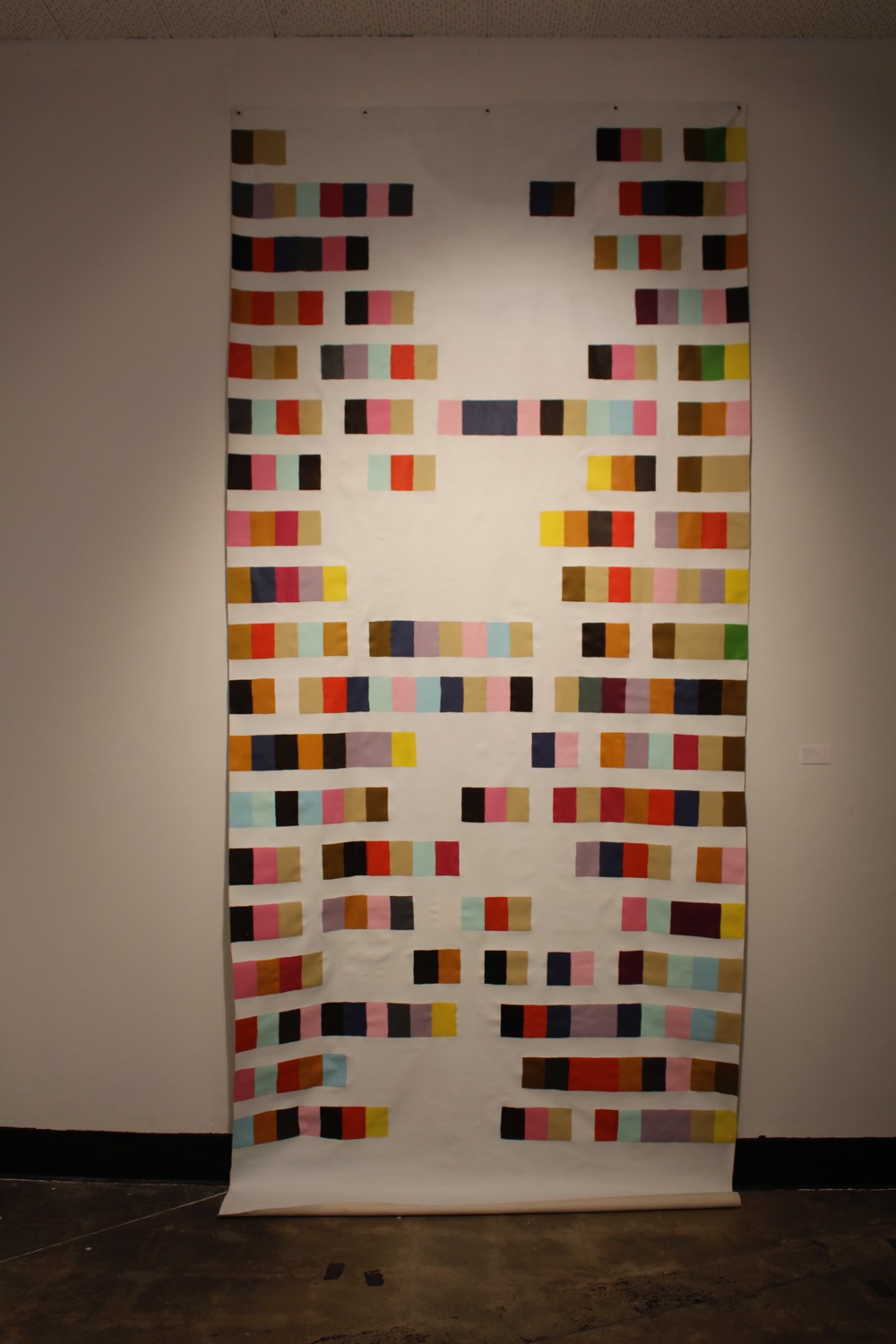

Devoid of that hegemonic separation, hermeneutics (revelation) and heuristics (creation) become synonymous activities. Such is the case with Leora Lutz’s multi-component project, anthem, created specifically for the biennial, which plays fast and loose with the basic morphological building blocks of phoenetically-coded languages. She does this primarily by using colorlittera, her own synaesthetically-inspired transliteration alphabet, developed by researching the history of industrial color names from sources such as Pantone, house paint brands, and the Plochere color system, which, because of the international nature of globalized commerce, allows for the standardization and cross-pollination of products between disparate communities. Starting from the poetic origins of the US and Mexican national anthems, historically constructed symbols of nationalistic identity, Lutz first fragments the English and Spanish lyrics into simplified concrete poems, then transliterates those spatio-linguistic forms into individual colorlittera blocks, and finally folds those blocks together to construct a linear structure oddly reminiscent of current methods for visualizing sequence data sets, including, and especially, genomic maps, transforming the entire project into a heuristic re-presentation of her own hybridized and acculturated identity, a product of being a US-born Caucasian woman raised by a politically-active Chicano step-father.

In his performative concert, Imperialistic Picnic, John P. Hogan, like Lutz, also purposefully conflates heuristics with hermeneutics, though doing so on a much larger ‘stage’ by moving beyond personal autobiography to grandiose historical macro-narratives for inspiration. In an hour-and-a-half long presentation, Hogan energetically jetted back and forth across the outdoor amphitheater at the center of the Cerritos campus, taking on numerous incongruent, but revelatory, roles. These included a monk preparing and distributing Thanksgiving-inspired turkey sandwiches against a backdrop of looping/droning electronic feedback noises, a 1960s-style folk singer wearing a Clint Eastwood mask melodically crooning an impassioned word-for-word reading of Ann Romney’s speech to the 2012 Republican National Convention, and a semiotics instructor lecturing on the historical signification of apples, corn, and potatoes before enacting a ritualized sacrament with bottled salsa that fused the sacrificial and cannibalistic symbolism prevalent in both Aztec human dismemberment and the Catholic Eucharist.

Interspersed between these scenes, Hogan donned his signature morion helmet in order to impersonate and/or channel Ponce de Leon, the mythohistorical conquistador of Florida and Fountain of Youth fame, as well as the lead singer of Hogan’s eponymous rock band, Ponce de Leon. Writhing on stage with, and against, a plastic palm tree, Hogan belted out songs from the band’s playbook, most notably Local Virgins, which features lines about the ambiguous complexities of imperial conquest, including “a new landscape calls into question my reality,” and “find a local virgin / one of those native squaws / tell her Jesus loves here / despite her many flaws” and, “all that you need know is that I am blessed and you are cursed / for every villain of my tribe, the best of yours is worst,” and, even more provocatively, “here is a girl / she can’t be more than twelve years young / eyes as grey as slate and canker sores on her tongue / her hair is matted, teeth are rotten; gritty odoriferous / there’s cobwebs on her ears / and a spider on her clitoris.” By using his own body as a public avatar for this revolving cadre of character-positionalities, Hogan affectively questions the way historical narratives of Self and Other are manifested in our own everyday lives, but also the way history itself is repeatedly (re-)inscribed through contemporary enactments, providing the possibility to alter the trajectories of those narratives going forward. In a sense, the writing of history can never be complete(d); it is always escaping from the clutches of its own imperialistic proclivities, just as, and perhaps because, the bodies that enact such histories in the present ontologically overflow themselves as well.

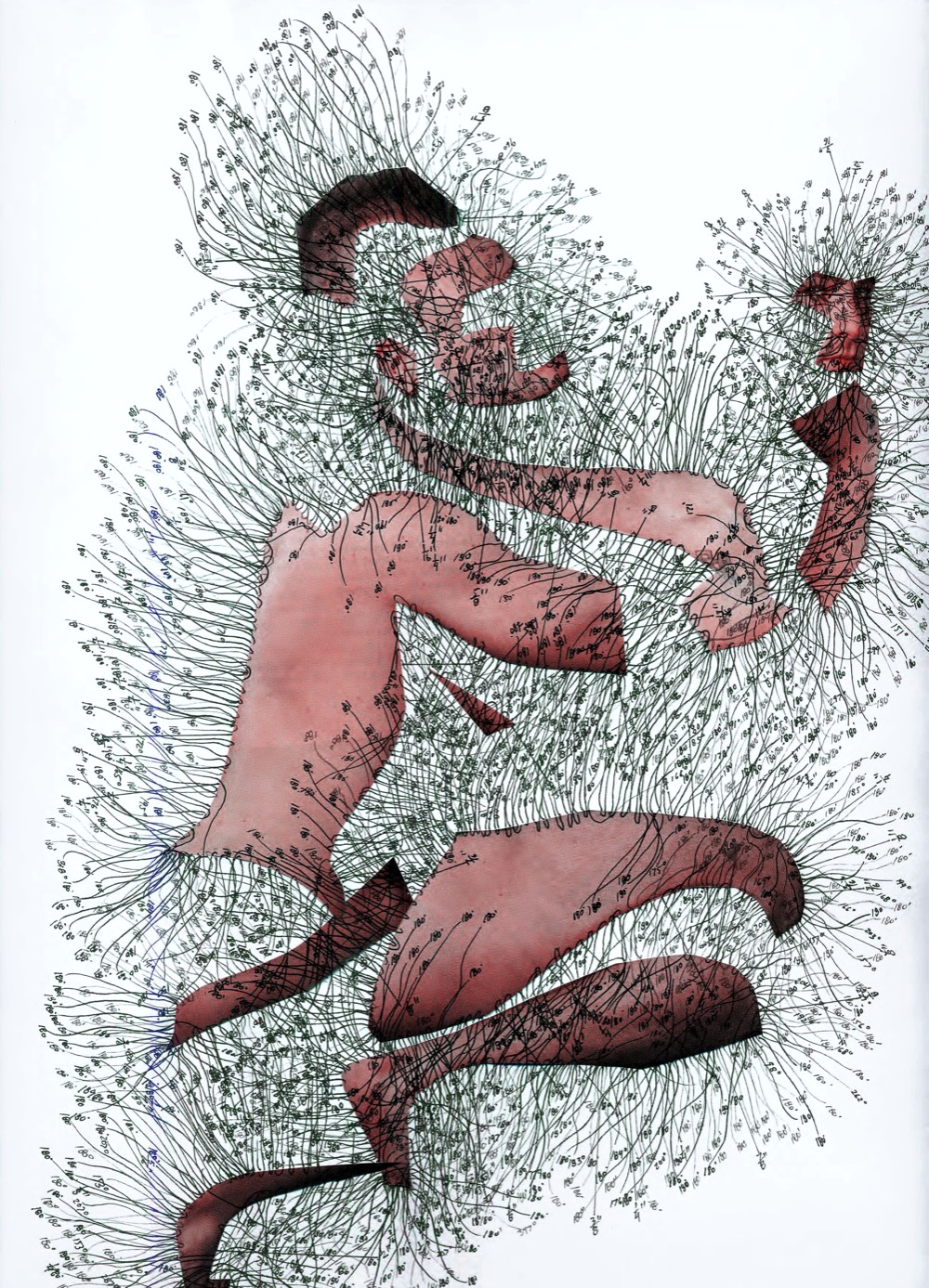

This existential excess of the body is further emphasized in the exhibited work of Enrique Castrejon, which specifically plays off the complex conventions of cruising and anonymity in the shared histories of gay desire and queer identification by dissecting images of scantily clad male bodies (“masseurs,” bears, twinks, jocks, and studs) and reassembling collaged fragments thereof with linear elements that visually link the photographic representations with overlaid numerical signifiers of measurement. The empirical positivism implied by the repetitious quantification of the bodies is here counterbalanced by the obvious pleasure the artist (and the viewer) gets from obsessively scrutinizing the minute details of these idealized male forms. This (con)fusion of sexualized aestheticization with biopolitical gaze transforms the work into a paradoxically affective/affecting biogram – simultaneously a diagrammatic re-presentation and a desirous abstraction that inevitably falls apart in “the gaps between positions on the grid” constructing a body that is( not); “a theoretical no-body’s land.”16

Specifically because bodies matter, they can never be fully material(ized); they are always-already virtual as well, which means that there is always more ‘there’ there. “They are excessive; their traces a by-product that can’t be used [up] by the system.”17 This excess is present even in an age of compulsively avaricious surveillance, where the photographically reproductive nature of a video feed can now be easily overlaid with, and dynamically augmented by, algorithmically-derived information, such as facial recognition or gait analysis. Bodies are excessive specifically because they are relational, just never monogamously so; bodies are relational to themselves and relational to other bodies, as well as relational to both mediated representations and analytical abstractions, such that “the relational body is populated by virtual intervals. Yet these shifting intervals are also always in a state of disappearance.”18 Because bodies exist in space and time, different relative positionalities can be ex-pressed at different moments and in different locations.

However, this surplus of potentiality need not imply complete indeterminacy. Bodies, in their endless relativity, still tend towards the direction of most profound gravitational pull and that (self-)attraction is afforded by the specific contexts of specific bodies inscribed specifically, through repetitious action. In the performative reading of her autobiographical essay, Radical Narcissism, Raquel Gutiérrez marks the powerful reflexivity that comes with acknowledging the authenticity of one’s lingering specificity and the revolutionary (self-)love made possible by (re-)tracing the narratives of shared communal experiences:

No one is told they are a baby man. Or a baby woman. You’re a baby. Then a boy. Or a girl. Then a man or a woman. It’s different with butch. With femme. I cling to these two categories the way we cling to a 2-party political system. We know that there are so many other ontological possibilities. I know that queer oedipality has rendered these categories moot. Still, I put so much hope and longing into what they could possibly be and do for us, and then the heartbreak, inevitable. But I return to this one. I inhabit butch. Warts and all.19

Bodies may be theoretically relative, but they are lived absolutely. Embodied experience, as Gutiérrez’s poetic prose makes clear, is the chiasmic confluence of outside-in and inside-out, the space in-between the past-present and the future-now.

Cognizant of this spatio-temporal relativity of memory and the resultant simultaneity of our own (dis)appearance, Matt Lucero produced an innovative form of representational object, existing somewhere between contact print and terrestrial repoussé, in order to capture the present state of a seemingly mundane, but historically-relevant (both personally and collectively), physical space. By spraying fiberglass onto the ground, the artist was able to take a topographic reading directly off the asphalt surface of a street in East Los Angeles where unused train tracks remain embedded in the center of the road. Specks of secreted residue are enmeshed in the largely colorless crystalline form, fragments of rubbish picked up and encased in the fiberglass like mosquitos in amber waiting to reveal their partial DNA, to be completed by our abstracted assumptions of the past in the present moment. Much like the Surrealist practice of frottage, a rubbing of surfaces meant to draw out hidden imagery from the unconscious mind in order to enact a psychoanalytic catharsis, the loaded historicity of the street is pushed into the object by the artist himself, specifically through his revelation that his own grandfather had helped to the lay tracks for the Union Pacific Railroad, that building block of American industrialization and continental imperialism; tracks much like those that are now slowly disappearing in the street, still partially visible in the artist’s imprint, through lack of use and sedimentary layers of new asphalt.

This entropic intersection between the personal and the collective is the basis for another project included in the exhibition at Cerritos, one which likewise focuses on the shared spatial(ized) trajectories inscribed across southern California’s roadways. Presented as a psychogeographical intervention, the Cog•nate Collective’s Borderblaster (Cerritos) exists as an extension of their previous social practice-oriented Borderblaster project at the San Ysidro port of entry along the border between San Diego and Tijuana. And, like that earlier intervention, the project for Cerritos centers around their signature mobile listening station, a rasquachismo-style assemblage of Radio-Flyer wagon, stacked wooden crates, guitar amplifier, tablet computer, and giant piggy-bank, all held together by tightly-wound rope.

While the earlier Borderblaster presentation had looped audio recordings of interviews with border crossers and shop proprietors in the Mercado de Artesanías de La Línea, the project for Cerritos streams an audio playlist for an imaginary commuter d(é)rive along the interstate freeway system between San Diego and Cerritos itself, focusing on the automobile as a ‘vehicle’ for “writing the text of the city” (or in this case the region), an embodied form of mapping described by Michel de Certeau in The Practice of Everyday Life.20 This auditory cartography remains distinct from similar lines made by walking in the work of other artists, such as Richard Long (in the landscape) or Jeremy Wood (in the datascape), since the mixtape here unfolds as both a displacement of the macro-territory of the highway system into the micro-territory of the gallery through the mobile listening station and the construction of the listener into an augmented flâneur, cognitively influenced in their journey by the aural ‘instructions’ of the playlist, available for download online, which includes location-specific sounds, like songs with lyrics featuring cultural icons, such as Chicano Park in San Diego and the migrating swallows of Mission San Juan Capistrano, as well as recordings made by Cerritos College broadcasting students highlighting the 'points-of-interest' in their own micro-commutes to and from school.21

Accompanying the sound component within the gallery space, a set of minimally-illustrated maps chart the various signal ranges of notable Borderblaster radio stations, produced by massive antennas strategically located on the Mexican-side of the border, projecting their invisible waves of sound far into the United States. In marking the important cross-highway placements of deferred border patrol inspection checkpoints, in San Clemente (along the 5 Freeway) and Temecula (along the 215 Freeway), against the relative signal strengths of the Borderblaster stations themselves, these maps also serve to highlight the actual distributive nature of all borders (i.e. customs gates within international airports spread throughout the country) and therefore functions as a pedagogical device “to endow the individual subject with some new heightened sense of its place in the global system”22 In effect, the border is shown to not simply be here or there; it is, in fact, everywhere, such that border subjectivities are also fragmented and distributed exponentially throughout the entire region.

In this regard, border subjectivities are in a state of perpetual precarity; and, as such, they are part of the larger, and increasingly common, class of the precariat. As Isabell Lorey explains, “certainly the situation of migrants has long been and still is precarious, as is living and working for anyone who doesn’t count as a citizen. I use the term ‘precarity’ (Prekarität) as a category of order that denotes social positionings of insecurity and hierarchization, which accompanies processes of Othering.”23 In an era of declining union-backed corporate pensions and governmental safety nets, along with increases in freelance labor forces and post-Fordist digital prod-usage, more and more people are joining the ranks of this precariat class, existing in various states of dehumanizing insecurity that often necessitates migratory displacements - from job to job, as well as from place to place.

In order to emphasize this link between migration and precarity, especially in the service-based workforce, the Break+Pausa collective, in conjunction with TeAda Productions and the Restaurant Opportunity Center of Los Angeles, produced TEST KITCHEN: Round 1 “In Between Jobs,” a Brechtian-style theatrical action that purposefully broke down the distinctions between performer and spectator, with its primary audience being a group of multi-ethnic culinary students from Cerritos College. Using score-cards as performance prompts, both performers and students, still dressed in their white kitchen uniforms, improvised interactions, filling the on-campus Falcon Room Restaurant with immigrant worker testimonials, a cacophony of kitchen sounds, and visuals of repetitive work gestures. Like a collective re-enactment of Martha Rosler’s 1970s feminist performance video, Semiotics of the Kitchen, Break+Pausa’s TEST KITCHEN gained power through its gestural ambiguity. A gesture, as defined by Giorgio Agamben and explained by Nermin Saybasili, occurs when “a simple fact becomes an event that is itself an end … involving the process in which ‘nowhere’ emerges as ‘now-here,’ the invisible gains its visibility, the non-presence its presence, the there its here-ness, and the immaterial its materiality.”24

By visually and sonically materializing the invisible conditions suffered by the customarily disposable populations of the precariat, the ensemble produced humanist value where it is all too-often ignored; by humanizing the frequently dehumanized food-service laborers and centering their marginal(ized) experiences. As Judith Butler points out, moving beyond Marx’s critique of capitalist alien-ation in his essay ‘Estranged Labor:’

[i]t is always possible to say that the affective register where precarity dwells is something like dehumanization. And yet, we know that such a word relies on a human/animal distinction that cannot and should not be sustained. Indeed, if we call for humanization and struggle against “bestialization” then we affirm that the bestial is separate from and subordinate to the human, something that clearly breaks our broader commitments to rethinking the networks of life.25

To radically ‘rethink the networks of life,’ as Butler suggests, especially with the goal of generating a sympathetic understanding between beings that/who are not alike, means, ultimately, challenging long-established anthropocentric world-views. Like Latino, the category of ‘human’ certainly exists, even if it is only because we, as human beings, say it does, but that leaves open the ethical quandary of how we might ‘police the border’ between not only who, but also what, might count as human; especially with the growing recognition, thanks to object-oriented philosophy’s recent assertion of a flat ontological ecology, that it is not just human bodies that are relationally constituted via their potential reversibility, making them therefore excessive and virtual, as previously discussed. In fact, this state is also the chiasmic condition of the ‘bodies’ of every ‘thing,’ be they independent objects or massed assemblages or, as is nearly always the case, both. The goal of this particular way of (re)thinking the networks of life is not, as some might fear by its loaded name (i.e. object-oriention), to objectivize the human, but rather, just the opposite, to grant to objects that which has traditionally been reserved conceptually to the perceiving human-being. In effect, an object-oriented (alien) ontology posits a populous and decentered ecosystem of living, vibrant matter, not a universal binary of dead stuff and conscious beings.26

In his recent book, Alien Phenomenology, or What It’s Like to Be a Thing, digital culture theorist Ian Bogost, playing off of Thomas Nagel’s 1974 similarly-titled essay, ‘What Is It Like to Be a Bat?,’ proposes the use of the term units to describe any and all actors/actants within a networked assemblage.27 Units are both singular and amassed. They are swarming swarms. They are forever alien and yet phenomenologically, existentially, familiar to one another. They are human, animal, vegetable, mineral, as well as human-animal-vegetable-mineral and any variation in between. Or, as Deleuze and Guattari put it, “you are longitude and latitude, a set of speeds and slownesses between unformed particles, a set of nonsubjectified affects”28

A number of works in the exhibition at Cerritos play off this growing recognition of previously suppressed (non-)entities within the ethical strata; be they animal, vegetable, or mineral. Daino (Dan Torres), for example, through his project We Come in Peace, partners with a living colony of ants from his own backyard to explore “the emergence of the living animal’s role as itself – instead of, or at least in addition to, animal imagery’s more traditional symbolic role.”29 He does so playfully, producing miniature protest signs rubbed with bee-pollen, which are then picked up and carried by the ants as they go about their daily ant labors.30 In doing so, he highlights, especially through his photographic documentation of this animal-centric performance, the slippage between the human-oriented content inscribed on the signs and the ironic failure of the ants to recognize, and properly react to, the revolutionary messages they carry.

In his transcribed lecture The Animal That Therefore I Am (More to Follow), Jacques Derrida ponders “‘Does the animal dream?’ Another way of asking, ‘Does the animal think?’ ‘Does the animal produce representations?’”31 Derrida gets to this point of asking what, and how, an animal might mean to/for itself, by first exploring what they think (or don’t) about us; or, rather, more to the point, what we think about them thinking about us and how the human is (regressively) produced from that reflexive ponderance:

Since so long ago, can we say that the animal has been looking at us? What animal? The other. I often ask myself, just to see, who I am – and who I am (following) at the moment when, caught naked, in silence, by the gaze of an animal, for example the eyes of a cat, I have trouble, yes, a bad time overcoming my embarrassment.32

In her Upside-Downers project, inspired, much like her weed projects discussed below, by issues of migration and displacement, Adriana Baltazar cast gold-encrusted paper-pulp blobs from the inside of cups and other recognizable everyday objects. These inversions are not only upside-down in their form, however, they are also carrying disconcerting facialized signs of consciousness, googly-eyes, that are at once visually ridiculous and existentially haunting. Like Derrida’s cat observing him in the buff, these non-things seem to ogle the viewer while simultaneously getting lost in their own, inaccessible, interiority. This withdrawal, similar to the oblivious ant-consciousness alluded to by Daino’s project, suggests a self-actualization for the non-human that is independent of human perception and metaphorical symbolism. But, again like Derrida’s cat, recognition of this withdrawal still produces an effect, and an affect, in the human perceiver and it’s in the denial of that (mutual) recognition that metaphor seeps back into the equation.

In her two recent weed projects, one of which was produced specifically for the exhibition at Cerritos, Baltazar collapses the metaphorical with the physical, using the plant itself as the starting point for both trajectories. Deploying the medium of crotchet, already loaded with historically-marginalized craft/feminist associations, she produced what appear to be yarn-bombed street signs hovering forlornly over woven-versions of location-specific species of weeds, which are revealed, even in their banality, to be visually stunning as aesthetic, formal arrangements, despite also generally being deemed undesirable (by humans). Both simulated avenues, 18th Street in Baltazar’s hometown of Chicago and Glendale Blvd in her newly adopted city of Los Angeles (Echo Park, specifically), are sites of immigrant congregation and community-building despite historic attempts at collective eradication through legislation and gentrification. Instead of manifesting the pejorative associations traditionally connected with the use of the term ‘weed,’ especially as a means to dehumanize immigrants, as highlighted in Otto Santa Ana’s study, Brown Tide Rising, where phrases such as “to uproot … the new crop … spring up … and weed out”33 are featured for their negative connotations, Baltazar’s 18th Street Immigrants and Echo Park Emigrants celebrate and champion the resistance and resilience of the much-maligned invasive weed, both as a biological organism and as a cultural signifier.

This mental trans-positioning of the human into the status of the weed might, therefore, be understood as a revolutionary attempt at (de/re)territorialization, a becoming-plant, certainly a becoming-imperceptible, existing somewhere between Deleuze and Guattari’s call for a becoming-animal, as seen in Daino’s project, and a becoming-molecular, as alluded to by Marisol Rendón’s. Reminiscent of a frozen moment in The Way Things Go, Fischli and Weiss’ 1987 video meditation on materialist interactions, Rendón’s It Seems It’s Going to Rain hovers in an evocative state of (un)becoming. Exploded and atomized bubbles engulf and/or extend the recognizable domestic object of the black side table, itself transformed by its existence in this incomprehensibly perpetual instant of de/construction, where the amorphous fog is given solid form and it radiates outward with an inner glow. A similar in-between-ness is revealed in the vivacious inhale and exhale of the checkerboard-arranged pillows of Rendón‘s Huff and Puff, from the same series. Like many of the other works included in the exhibition at Cerritos, through Rendón‘s object-oriented foci, the “cutting edges of deterritorialization become operative and lines of deterritorialization positive and absolute, forming strange new becomings, new polyvocalities.” They demand that we the viewers, because they function themselves in this self-same manner, “become clandestine, make rhizome everywhere, for the wonder of a nonhuman life to be created.”34

Addendum: To Whom It May Concern

(Daino image)

Buildings speak, though not commonly in a language humans choose to recognize. So

people have developed a habit of marking up buildings; they add signs, denotational

and connotational alike. Daino’s outdoor installation for the SUR:biennial at Cerritos

College plays off this tradition, but with a purposeful and provocative twist. Instead

of the signature-style tag of graffiti-culture, including ASCO’s infamous 1972 Spray

Paint LACMA, which transformed the entire public art museum into the Chicano collective’s

‘work,’ Daino’s To Whom It May Concern renders barely legible typographic forms out

of wooden elements painted to match the building’s wall, rather than contrast with

it, such that the words seem to emanate from, and out of, the structure itself, an

alien annunciation (only if we chose to ignore it). It seems appropriate to end this

essay on Daino’s piece, since, in its very language, his project announces the beginning

of a dialogue, rather than its completion. Likewise, the 2nd Los Angeles SUR:biennial

is meant to provide an opening into the ongoing conversation(s) about cultural classification

and artistic production throughout this entire region that we might, one day, acknowledge

as SUR.

Endnotes

1 Philip Kennicott, Art review: ‘Our America’ at the Smithsonian, Museums, Washington Post, 25 October 2013.

Web. 28 December 2013 http://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/art-review-our-america-at-the-smithsonian/2013/10/25/77b08e82-3d90-11e3-b7ba-503fb5822c3e_story.html

2 Philip Kennicott, Alex Rivera, Philip Kennicott debate Washington Post review of ‘Our America’, The Style Blog, Washington Post, 1 November 2013. Web. 28 December 2013 http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/style-blog/wp/2013/11/01/alex-rivera-philip-kennicott-debate-washington-post-review-of-our-america/

3 Robin Cembalest, Adrian Piper Pulls Out of Black Performance-Art Show, Web Exclusive, ARTnews, 25 October 2013. Web. 28 December 2013 http://www.artnews.com/2013/10/25/piper-pulls-out-of-black-performance-art-show/

4 Kennicott, Alex Rivera, Philip Kennicott debate Washington Post review of ‘Our America’, Ibid.

5 Rasheed Araeen, Art and Postcolonial Society, in Globalization and Contemporary Art, ed. Justin Harris (Miniapolis: Minnesota University

Press, 2011), 373.

6 Ibid., 366.

7 Exhibit A: Kogi Korean BBQ Taco Trucks!

8 W.J.T. Mitchell, World Pictures: Globalization and Visual Culture, in Globalization and Contemporary Art, ed. Justin Harris (Miniapolis: Minnesota University Press, 2011), 262.

9 It’s telling to note that, because of normalized cartographic orientations placing the Artic at the top of the globe, the original snapshot taken by the crew of Apollo 17 was actually flipped by NASA before it was released to the general public, a sad pastiche of Joaquín Torres García’s 1943 drawing América invertida (Inverted America).

10 Louis Althusser, Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses, in Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, trans. Ben Brewster (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2001), 118.

11 Eve Meltzer, Systems We Have Loved: Conceptual Art, Affect, and the Antihumanist Turn (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), 181.

12 Etienne Balibar, Structuralism: A Destitution of the Subject?, Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies (Vol 14, No 1, Fall 2003), 17.

13 This visual and conceptual resemblance is most striking, and most telling, with the 18 unit series of Kelly’s Post-Partum Document called Documentation VI, Previewing Alphabet, Emergence and Diary from 1978, which itself notably resembles the structure of that famous decoder tablet, the so-called Rosetta Stone.

14 Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (London: Routledge, 1996), 173.

15 Gilles Deleuze, “How Do We Recognize Structuralism?,” trans. Melissa McMahon and Charles J. Stivale, in Charles Stivale, The Two-Fold

Thought of Deleuze and Guattari (New York: Guilford Press, 1998), 263.

16 Brian Massumi, Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation (Durham,

NC: Duke University Press, 2002), 3-4.

17 Meltzer, 186.

18 Erin Manning, Relationshipscapes: Movement, Art, Philosophy (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2009), 18.

19 Raquel Gutiérrez, “Radical Narcissism – Part 1 of an Essay”, Blog, Raquel Gutiérrez, 4 January 2013. Web. 30 December 2013 http://raquelgutierrez.net/blog/2013/1/4/radical-narcissism-part-1-of-an-essay

20 Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven Rendall (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), 91-92.

21 Misael Diaz and Amy Sanchez, Compilation for Commute, Cog•nate Collective, SoundCloud, 24 October 2013. Web. 29 December 2013 https://soundcloud.com/cognate/cognate-collective-compilation

22 Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991), 54.

23 Jasbir Puar (ed.), “Precarity Talk: A Virtual Roundtable with Lauren Berlant, Judith Butler, Bojana Cvejić, Isabell Lorey, Jasbir Puar, and Ana Vujanović,” TDR: The Drama Review (Vol 56, No 4, Winter 2012: 163-177), 165.

24 Nermin Saybasili, Gesturing No(w)here, in Globalization and Contemporary Art, ed. Justin Harris (Minniapolis: Minnesota University Press, 2011), 418.

25 Jasbir Puar (ed.), 173.

26 Jane Bennet, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010).

27 Ian Bogost, Alien Phenomenology, or What It’s Like to Be a Thing (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012).

28 Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (London: Athlone, 1988), 262.

29 Steve Baker, ARTIST | ANIMAL (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 8.

30 James MacDevitt, We Come in Piece(s): Alien(ated) Phenomenologies and Cultural Resistence in the Biopolitics of a Human-Insect Assemblage, in Daino, WE COME IN PEACE (Cerritos: Blurb, 2013).

31 Baker, 208.

32 Jacques Derrida, The Animal That Therefore I Am (More to Follow), trans. David Wills. Critical Inquiry (Vol 28, No 2, Winter 2002: 369-418), 373.

33 Otto Santa Ana, Brown Tide Rising: Metaphors of Latinos in Contemporary American Public Discourse (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002), 89.

34 Deleuze and Guattari, 191.

Adriana Baltazar

Adriana Baltazar’s life is rooted in Chicago, where she was born and raised. Baltazar holds a BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and is currently a 2nd year candidate in the MFA program at CalArts. Her work has been presented in various group exhibitions, including at the Woman Made Gallery, Antena Gallery, River East Arts Center, Estudio Tres, City of West Chicago Museum, and the National Museum of Mexican Fine Art. In 2006, Baltazar was a recipient a Chicago Community Arts Assistance grant for a project inspired by the work of community pillars that are everyday people in the communities of Pilsen and Little Village, Chicago. In recent years, she co-founded Cobalt Studio in Chicago and served as a co-director/curator (2010-12) to feature contemporary art that is relevant and engaging to Chicago’s Pilsen community.

STATEMENT

My current work focuses on inquiries and investigations into the often overlooked traces and marks of our histories, as they fall to the way side and simultaneously unravel everyday in the urban environment. As a child and adult, witnessing the US the response of increasing Mexican immigration with discriminatory legislation, and corresponding opposition to them through protest and demonstrations, one message stood out amongst the chants and sea of handwritten signs. Who are you calling an alien, pilgrim? I remember seeing it for the first time in the 1990s as a sign and then as t-shirts and stickers. It’s tone, one of wit and implication always seemed so striking to me. It seems to be asking that we pick a side. But, with either side functioning as an other there is really nothing to lose or to gain. It serves as a reminder that we are all others. 18th St. Immigrants (Dandelion, Chicory, & Thistle), 2011 and Echo Park Emigrants (Fennel), 2013 are meditations on our relationship to the other. Overlooked and neglected pockets of the natural environment tell stories of otherness. Beyond the otherness of the natural world versus our constructed one, these common weeds are traces that mark paths of European emigration. The invasive species carry the history of a culture that once revered them for their herbal and medicinal purposes. Our relationship to common weeds such as these, reflect a similar conflict in the way we regard and value one another as domesticated and/or native.

Break+Pausa (Christina Sanchez & Cayetano Juarez), Test Kitchen: Round 1 "In Between

Jobs", Performance, November 7, 2013 : Falcon Room Resturant.

Break+Pausa (Christina Sanchez & Cayetano Juarez)

Cayetano Juarez hails originally from Oaxaca, Mexico, and has spent over fifteen years crafting delicious meals in a plethora of California restaurants. Christina Sanchez is a socially and politically engaged artist working in the public sphere on projects that address social justice for underserved communities. She holds a BA in Studio Art from San Francisco State University and a MFA in Public Practice from the Otis College of Art and Design, where she was awarded the inaugural Public Practice teaching fellowship in 2012. Her discursive practice operates at the intersection of performance, community organizing, and popular education to investigate how collectivity and the arts can merge to acknowledge the issues of the working poor and bring about social change. In 2011, Juarez and Sanchez co-founded the Break+Pausa project as a long-term, Los Angeles-based artistic and culinary inquiry into the lives of immigrant restaurant workers.

STATEMENT

Through informal interviews, performative interventions, and shared meals, our ongoing series of projects act as a form of civic pedagogy meant to engage workers, students, food advocates, labor organizers, and people who love to eat out alike, in developing a worker-centered philosophy to living and eating ethically.

Enrique Castrejon, Anonymous Trick #4, Collage & Ink, 11" x 14", 2011.

Enrique Castrejon, Anonymous Trick #4, Collage & Ink, 11" x 14", 2011.

Enrique Castrejon

Born in Taxco Cuerrero, Mexico, and living/working in Los Angeles, Enrique Castrejon holds a BA in Chicano Studies from Cal State Northridge, a BFA in Sculpture from Art Center College of Design, and a MFA in Studio Art from California Institute of the Arts. Castrejon’s work has been exhibited in solo shows at the Museum of Latin American Art, Bermudez Projects, Gallery A300, and Millicent Gallery, as well as in group exhibitions at LA Art Core, the Traveling Gallery of Contemporary Art in Phoenix, LA Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE), the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery at Barnsdall Art Center, and the Armory in Pasadena, among many others. A disease intervention specialist at the LA Gay & Lesbian Center, as well as a former Program Coordinator at LACE, Castrejon has also served as a featured panelist on KPCC’s Air Talk with Larry Mantel on the topic of Chicano Art & Pacific Standard Time exhibit, alongside other notable participating artists, Gronk, Patissi Valdez, and Sonia Romero. In addition, running simultaneously with the SUR:biennial, his solo exhibition, Axiom of Solitude: Investigations & Meditations, was recently on view at Bermudez Projects and his work is also currently included in a nationally-traveling group exhibition titled Out of the Rubble, organized and curated by Susanne Slavick, that looks at how artists have “reacted to the wake of war – its realities and representations.”

STATEMENT

Images of beauty, queer bodies, HIV, war, death, destruction and tragic current events are elements that inspire my work. I work by linearly dissecting and cutting appropriated images found in magazines, newspapers, art catalogues and online sources into smaller identifiable geometric shapes, so that I may then investigate and describe what I see through measurements. This selected graphic imagery is transformed into quantified drawings mapped by measuring distances between points (x inches), calculating the varied angle degrees created within the shapes (360˚-A˚= B˚), and/or written data related to the image of each shape. Measurements or other definable data or units are inscribed along the side of the shapes to question and describe what I see. These precise measurements abstract the image, interfering and altering its fixed meaning, creating other possible interpretations through this linear dissection. In creating these fragmented and measured drawings from the parts of the whole, I hope to challenge our perceptions of what is real, forcing the viewer to think critically about information that is constantly bombarding all of us in our everyday lives through images selected in directed advertisements, pop-culture sources, editorials and news stories found in printed and online media.

Cog•nate Collective, Borderblaster (Cerritos), 2013. Installation Shot

Cog•nate Collective (Misael Diaz & Amy Sanchez)

Cog•nate Collective is a bi-national arts collective conducting research and developing site-specific community-based projects, primarily at the US/Mexico border. Their work analyzes and documents the construction of socio-economic relationships at the border, focusing on migration patterns of people and goods, as well as the cross-border production, distribution and consumption of cultural products. Based in the Mercado de Artesanias de la Linea, an artisan market located between the lanes of US-bound traffic at the San Ysidro Port of Entry, Cog•nate has developed and carried out site-specific interventions in collaboration with local artists, shop owners and pedestrians at the crossing. These have included bi-national exhibitions, a workshop series for children at the crossing, an artist exchange/residency with Montreal-based art center Dare-Dare, and an artisan residency with Mujeres Mixtecas, a Tijuana collective of indigenous artisans. Cog•nate has participated in public programs at the San Diego Museum of Art, and Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego. The collective's most recent exhibitions include Living As Form (Nomadic Version) at UCSD's University Art Gallery and Divested Interest: Exchange Dialogues with Cog•nate Collective and Ramiro Gomez at Grand Central Art Center. For the next year Cog•nate will be in residence at Grand Central Art Center in Santa Ana. Cog•nate Collective is coordinated by Amy Sanchez and Misael Diaz, both Southern California-based artists, writers, and arts educators. Misael Diaz holds a BA and MA in Latin American Studies from UCLA, as well as a MFA in from UC San Diego. Amy Sanchez has a BA in Art History/English from UCLA, and is currently a MFA candidate in Critical and Curatorial Studies at UC Irvine.

STATEMENT

Our most recent endeavor, Borderblaster, is a hyper-local radio station which brings together the voices of vendors, artisans, artists, and activists in a series of conversations, readings, and interviews reflecting on processes of migration. Borderblaster takes its name from the title given to radio stations that transmit their signals at very high power between nations (e.g. San Diego radio stations that broadcast from Tijuana). Unlike traditional border blasters, this project localizes the transmission to micro-environments shaped by migration. The first iteration of the project Borderblaster (SD/TJ), 2012, commissioned to be a part of Living as Form (Nomadic Version) at the UCSD University Art Gallery (UAG), focused on the (dis)junctures experienced at the San Ysidro Port of Entry during the process of crossing the border. It brought together the voices of vendors, artisans, artists, and activists in a series of conversations, readings, and interviews that reimagined cultural engagement at the crossing. The series was recorded and transmitted from inside of the Mercado de Artesanias de La Linea on 87.9 FM to cars, and using the “Mobile Listening Station” sculpture to pedestrians. The second iteration of the project Borderblaster (SNA), 2013 was created during the exhibition Divested Interest at Grand Central Art Center in Downtown Santa Ana. The project consisted of a series of oral histories and interviews with local residents, artists, community leaders and business owners reflecting on the economic, social, and cultural dimensions of redevelopment in the Downtown core of Santa Ana, culminated in an audio excursion that explored the history of the area, its ties to Mexican migration and the physical/psychological divides caused by redevelopment. For Borderblaster (Cerritos), 2013, we invited Cerrito College Students to contemplate an act of migration they make on a nearly daily basis: their commute. The etymology of the word commute is associated with both the act of movement and a form of exchange. With this as basis, we asked students to produce short audio records of “local points of interest” on their path to school, as a way of reflecting and prolonging psychological exchanges with the urban landscape that happen in transit. We then assembled a “mix-tape,” timed to match our a commune from the Border to Cerritos College, combining a selection of music that speaks about this commute, spatially and symbolically, with recordings from major border blasters radio stations in San Diego/Tijuana, specifically Jammin Z90 (90.3FM), 105.7FM The Walrus and 91X (91.1FM), recordings from commuter stations in general, with a focus on WPMD 1700, the college’s radio station, and the student produced recordings of local points of interest. The resulting audio was presented in the gallery using the Mobile Listening Station, accompanied by signal maps of the various border blaster stations, and was also made available for download via SoundCloud.

Daino, We Come In Peace Series, 2011-2013.

Daino

Born in El Salvador, Dan "Daino" Torres, lives/works near downtown Riverside. He is a multimedia artist and the founder/publisher of the e-zine Plastic Water. His work has been exhibited at, and is included in the permanent collection of, the Riverside Art Museum and the UCR/Sweeney Art Gallery. Daino studied at the California Institute of the Arts, from which he did not receive a MFA.

STATEMENT

For his latest, and quite timely project, We Come In Peace (2011-2013), the artist Daino enters into a temporary zone of proximity with a colony of ants living in the dirt just outside his Riverside, California home. Rather than displace them into his studio space, Daino comes to them, into the environment that they have built for themselves; uninvited, for sure, but not necessarily unwelcome either … for he comes in peace. He’s not there to wipe them out; his intent is not aggressive. He’s not there just to observe them at a distance either, a hyper-intelligent human being dispassionately translating and abstracting the inscrutable laws of Nature. No, he’s there to participate with them; to play with them; to join their network; to swarm together. Their environment might be limited, but it constitutes a world and, by entering it, he becomes a part of it. It is foreign, but not necessarily distant. His scrutiny and their engagement together represent an assemblage, as Deleuze and Guattari would call it, of “becoming-insect.” The photographs and videos that he produces from this mutual engagement serve as a document of his ongoing performative project, a project which itself functions as part hermeneutic research and part heuristic intervention. By learning the daily routines of the ants, through repeated exposure to their activities, particularly their collective investment in aggregating bodily fragments of dead bees (and the pollen/honey that they carry), Daino is able to entice the ants to individually and collectively carry small replicas of protest signs scrawled with dialogically anti-authoritarian messages. This tongue-in-cheek, and yet completely sincere, effort to reference swarming’s influence on contemporary strategies of dissent (Tahrir, Occupy, social media, etc), at the same time, highlights the failure of any reversal of that influence. However altruistic his intent, he cannot teach the ants to reject their insect motivations. There is no ant version of Marx waiting in the wings to cry out “Worker( Ant)s of the World, Unite! You Have Nothing to Lose But Your Chains.” The irony inherent in the project is that by voluntarily picking up the signs that protest inhumane treatment, celebrate transcendental love, or express solidarity with an anti-corporate agenda, the ants are always, in fact, continuing uninterrupted and unmoved in their daily insect labors. What the visual documents from this joint performance ultimately make clear is that Daino never really trained the ants at all, rather they’ve trained him, and specifically through their resistance to his attempts at personification. Their methods for carrying the signs, in their mandibles and usually by the paper end, rather than the stick, along with the way the inverted, cropped, or invisible lettering tends to obscure the actual message from our view, is the real manifestation of their protest. They reject Daino’s efforts at humanizing them, they refuse his authority, as evidenced finally by the stack of mini protest signs outside the entrance to their underground layer. After taking the signs with them into that private and inaccessible space, they ultimately spit them out again, unwanted and unnecessary objects, abject waste. Our own favored version of autonomous and agential humanity is alien to them, or at least alienated from them, but in their refusal of it, they embrace their own unique form of agential power nonetheless.

John P. Hogan, Imperialistic Picnic, Performance November 18, 2013. Falcon Square

Amphitheater.

John P. Hogan

John P. Hogan received a BFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art and a MFA in Art and Integrated Media from CalArts. He has exhibited and performed at venues including the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, Automata Los Angeles, Yerba Buena Center, Fritz Haeg’s Sundown Salon, the MAK Center, and Machine Project. In the Spring of 2013, Hogan performed Song of Yourselves at Automata Los Angeles. Conceived as an "Irish Wake for the Supremacy of the American White Male," this performance included poetry, music, re-performances of speeches from the 2012 Republican National Convention, and contextually appropriate karaoke songs sung by audience members. A publication in association with Song of Yourselves is forthcoming from Golden Spike Press. Hogan has also written about art and culture for Art:21 and his essay on the work of painter Ben White is included in the forthcoming book Ruin Upon Ruin from Insert Blanc Press.

STATEMENT

My work satirizes the grandstanding of dominant ideologies, with a focus on male anti-heroes in situations that dramatize imperialistic, colonial, and institutional struggles. Archetypal characters lose their footing as they attempt to meet the demands placed on them by their belief systems. I point to these frailties in order to diffuse tensions and encourage empathy in discourse regarding privilege, power dynamics, and the individual’s role within institutions. I also am interested in the integration of entertainment culture with mythology, and the ways this is expressed in various American subcultures. I create expansive artworks engendering drawing, writing, pop music, performance, radio-plays, and video. My performance art seeks to evoke populist forms such as community theater and garage rock, which resist professionalization and celebrate untrained enthusiasm.

Nery Babriel Lemus, My Mother Did Not Come From Outer Space, Oil on Canvas, 41" x

47", 2013.

Nery Gabriel Lemus

Nery Gabriel Lemus received a BFA from Art Center College of Design and a MFA from CalArts, with additional training at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. His work has been featured is several recent group exhibitions including The Violent Bear It Away at Biola University, Made in L.A. 2012, organized by the Hammer in collaboration with LA><ART, OZ: New Offerings From Angel City at Museo Regional Guadalajara in Jalisco, Mexico, The Seventh House at Project Row Houses in Houston, Texas, the 2010 Border Art Biennial at El Paso Museum in El Paso, Texas, El Grito at The University of Arkansas in Little Rock, Arkansas, and Common Ground at the California African-American Museum. In addition, Lemus has had solo shows at Steve Turner Contemporary and Charlie James Gallery in Los Angeles. He is a recipient of a COLA Fellowship Grant from the Department of Cultural Affairs, Los Angeles, and the Rema Hort Mann Foundation Fellowship Award. Lemus is represented by Charlie James Gallery in Los Angeles.

STATEMENT

My recent projects have tended to be inspired by intrapersonal interactions between people. For example, one recent series focused on the influence, both positive and negative, adult men have over young boys, either within families or simply as role models within society. My interest in this particular topic stems from my own involvement in social work over the past 14 years, where I have worked with boys and young men with absent fathers and a lack of positive male role models. In addition, for the last couple of years, a number of my projects have addressed the divisions that exist between Latinos and African- Americans in Los Angeles. My intent with this work has never been to give a solution to the polemic, but rather simply to engage in a critical discussion that points to mutual and overlapping activities, reflecting a shared practice that might, through acknowledgement, absorb the acrimonious relationship between both tribes. In the painting, My Mother Did Not Come From Outer Space, part of a newly developed body of work, I attempt to break down the stereotype of the ‘illegal’ alien by conflating sci-fi culture with contemporary political rhetoric. The painting depicts a hypothetical image of the universe and implies that calling someone an alien should be limited to visitors from other planets and not in relation to fellow human beings.

Matt Lucero, Los Angeles Pacific Electric Railway Fragment, For the work My Grandfather

did on the Union Pacific Railroad, Composite, Fiberglass, and Resin, 120" x 76" x

4", 2008.

Matt Lucero

A graduate of the BFA program at UC Riverside and the MFA program at CalArts, Matt Lucero lives/works between Los Angeles and Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam, creating sculptural and performative works that challenge notions of private versus public space and explore notions of personal and historical narratives. His most recent works involve his collective, known as The Propeller Group, with fellow members Phunam and Tuan Andrew Nguyen. The three members produce collaborative art work, operate a commercial film production company called TPG, and run an artist-initiated contemporary art platform which they founded in Vietnam called Sàn Art. Their collaborative work has recently been included in No Country: Contemporary Art for South and Southeast Asia at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and The Ungovernables at the New Museum Triennial. The Propeller Group has also exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, the Hammer Museum, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Guangzhou Triennial, and the Singapore Art Museum.

STATEMENT

My work utilizes performance, installation, and intervention, assisted by commercial marketing and design strategies, to open a debate over consumption and public versus private issues of space, as well as the consequences of display and representation. The work included in the SUR:biennial was created from a cast of a section of street in East Los Angeles, where unused train tracks remain embedded in the center of the road. These fragmented remains are a byproduct of a failed transportation system that was in place in Los Angeles during the 1920s and can still be seen throughout much of the city. In a way, the piece speaks of personal, regional, and even nationalistic, histories, encased within in the lifeless and colorless form left behind from an imprint of the street, and, as such, the piece also functions as an effective metaphor for death, both personal and collective. At the time I made this cast, I was thinking of tying the physical fragments around me to the fragmentary memories I had of my grandfather and the narratives I had built up around those memories. In particular, I wanted to create a piece that honored the work that he did on the Union Pacific Railway in the early 1900s, one of the major building blocks of Industrialization in America. The demise of these tracks, therefore, does more than just highlight my own personal loss; they signal a collective one as well.

Leora Lutz, anthem (scroll), Acrylic House Paint on Canvas, 60" x 130", 2013.

Leora Lutz

Leora Lutz’ installations, sound works and objects shift ordinary understanding into flux to create new visual conversations and poetic narratives. The intangible and disappearing qualities of written and oral history become captured in her work through the presence of touch with a desire to make sense of the space between ritual and routine. Lutz’ professional background spans over 18 years as an exhibiting artist and art administrator. She holds a BFA in Art & Art History from Cal State Fullerton and is completing an MFA in Interdisciplinary Sculpture and MA in Visual & Critical Studies at the California College of the Arts. She is also currently a writing and art history learning facilitator for undergraduate students at California College of the Arts in San Francisco and is a regular art writer for the San Francisco Arts Quarterly. Her work has been shown at several galleries and institutions including the Henry Art Gallery in Seattle, Riverside Art Museum, MOCA Los Angeles, and the Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art in San Francisco. Her recent project if by sea: sound-poetic walk are site-specific sound pieces for Angel Island in conjunction with CCA ENGAGE and the Angel Island Conservancy. Lutz is also currently working on a project for the For-Site Foundation in Nevada City, California and a poetry exchange for an exhibition at the Belgrade Consulate in Serbia.

STATEMENT

My exposure to Mexican ideology began in 1981, when I was nine years old. My mother married a man from Mexico, and I became part of a large extended family still living there. As an American of Northern European decent, my Mexican heritage is a visual secret to the outside observer. I can only claim my Mexican identity through language - through explaining my affiliation with my stepfather’s family. Eduardo and Dolores Venegas fled Mexico during the enactment of the 1917 Mexican Constitution, which persecuted Catholics. Deeply devoted to their religion, they settled in Downtown Los Angeles where they found freedom to practice their faith. At the same time the US initiated the US Immigration Act of 1917, which included a caveat to deport citizens who did not speak English. My family managed to remain in Los Angeles, despite speaking Spanish as a primary language. Spanish isn’t really spoken at family gatherings now that the older generations are gone, but that in no way affects the family's identity. No matter what language is spoken, the meanings of identity still remain. This personal and family history has had me thinking recently about various extra-linguistic forms of identity expression, which brought me to the concept of the national anthem. Anthems are a form of music that is intended to help unite a nation or groups under a single ideology. Originally used in religious choral arrangements (predominantly until the 17th century), anthems are based upon the lyrics, the meanings and messages that the words convey while singing. The modern usage of the term is used for songs that define a culture or country's ideology through national anthems. National anthems define the ontology of the nation's citizens in unity through a single song. The etymology of the word anthem is a derivation of antiphone. Antiphonal music is music that is performed by two semi-independent choirs in interaction, often singing alternate musical phrases. In the installation Anthem, the scroll is an abstract, antiphonal transliteration of excerpted text from the United States national anthem and Mexico's national anthem. Words have been chosen through a complex system of aligning phrases from the text and then slowly eliminating words and sentences to create a poem. The order of the words in each national anthem has not been changed, and they run in lines from top to bottom - each anthem mirroring the other as if in conversation. They are written in Colorlittera, an international language I created which has the potential to unite anyone using it by putting them "on the same page." Accompanying the installation is an orchestral audio mash-up of both anthems and a small book that acts as a codex with texts in both English and Spanish.

Still from Andres Payan's Geophagy, 2011, 7:00 minutes.

Andres Payan

As a child born and raised in Mexico and educated in the United States, I quickly learned the stark differences between the two cultures to which I was being simultaneously exposed. I was forever crossing the border and interacting with both societies through my daily walk to school from Juarez to El Paso; a monotonous and insignificant action that becomes an abstracted idea through a repetitive action until it looses meaning. Thus the nature of the social structure in which I lived and was educated in, becomes one of the most important resources that continues to feed my creative process. Allowing me to focus on daily life and routines that define identity and social behaviors, but are often overseen by the individual. This can be seen, for example, in my investigations into monetary exchanges through the documentation of receipts that map the travels of an individual between both cities in order to highlight the invisible loss that occurs through the constant journey. Blurring ideas of nationalism by placing a rapidly growing bilingual population in a liminal space. A space that provides a constant trade not only of language and economies, but also of physical exchange and cross cultural influences. Allowing me to further explore ideas of culture hybridization in objects that exist within these spaces. Executed through the creation of laborious and complex objects that make use of traditional Mexican craft tactics and work methodologies, which by utilizing their intrinsic formal and material qualities allows me to emphasize their amalgamate nature and position within a larger web of trade and culture hybridization. It is these series of gestures, popular imagery, and actions, which serve as the basis of the greater investigations in my work. Utilizing the interstitial nature of the Juarez, Mexico and El Paso, Texas borderland to construct a snapshot of a larger world web of social shifts, with the traversing of political, social and cultural ideas. I am strongly focused on the hybrid character, the individual that develops a fragmentation in their daily living and to a sense an amalgamation of ideas, cultures, and social structures, allowing me to focus on how location, cultural ideas and paradigms either converge or clash within the individual, allowing them to develop a more fluid understanding of today’s globalized societies.