SUR:biennial 2013

SUR:Biennial > 2013

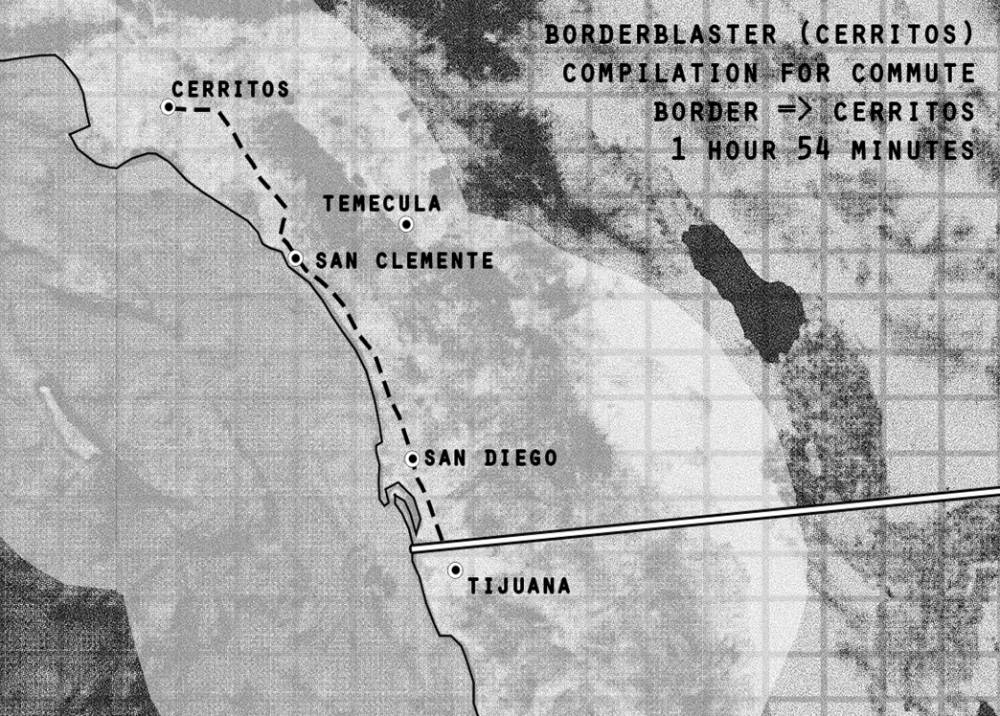

Cog-Nate Collective, Border Blasters Post Card (Front) 2013.

Polyscapes

Fragmentaty Themes on Collective unity

Para todos, todo. Para nosotros, nada.

It has been about twenty years since Francis Alÿs walked around Mexico City’s Centro Historico with The Collector, a magnetic dog that picked up scraps of metal off the sidewalks until it was completely smothered in its trophies. A few years later, Gabriel Orozco rolled a large ball of plasticene called Yielding Stone around the city so that whatever lay in its path would either shape it or get stuck to it. Both artists, and many others associated with this wave of Neo-Dada Mexican conceptual art, would continue to explore the idea that objects might capture the detritus, trophies, remnants, currency, and memory of a place.

This past October, Rio Hondo College students on their way to and from the library paused to consider Carmen Argote’s Senses at Auction, an arrangement of giant cartoonish facial parts nestled together in the middle of the grassy quad. It appeared that these gigantic appendages—a papier mache ear, eye, and clownish nose—had blown in out of nowhere along with a bright red tumbleweed. Appreciating the surreality of this visual situation, students snapped a few selfies with the sculptural group, but soon the sprinklers did their damage and the Senses were moved into the art building’s concrete-floored lobby. Here, the parts seemed to timidly arrange themselves even closer together, as if seeking comfort in this unfamiliar space. In the art gallery, Argote’s Polyscapes, large color photographs of the same huge eye and ear perched on the brown Ascot hills of Lincoln Heights were displayed. The appendages are reconstructions of props from the nonextant and long-forgotten Selig Movie Studio and Zoo once located in Lincoln Heights, the artist’s current neighborhood. Like the rescued body fragments of the Colossus of Constantine, the Polyscapes are reminders of ethereal but lingering presences and places, and evidence of the permeability of objects and their ability to cross physical and metaphorical borders of time and space. They reveal the process of (re)constructing a sense of place through memory and experience, providing a perfect metaphor for this year’s SUR Biennial.

Also at Rio Hondo, Emily Silver examines the space between the celebratory and the tragic in her Mexican-style metal vendor’s cart precariously piled with the leftovers of birthday parties and funeral flower arrangements. In this Untitled Upheaval, torn and twisted colored streamers, piñata fragments, paper hats, broken birthday candles, tacky quinceañera table decor, and a warped cardboard birthday cake decorated with cheap funeral flowers have been rescued from the trash pile after the celebration and covered in thick layers of silver frosting. Such works are invitations to revel in these comic, delirious, disappointing moments. Silver reminds us of the dreadful realization that, “the idea of it (the party) is so much better than being there.”

At the Torrance Art Museum, Alex Donis’s life-sized drawings of masturbating border patrol officers are arranged in a large circle, creating a literal circle jerk entitled Sueños Mojados. The artist explained that this concentrated place of sexual desire is a space that doesn’t really exist. The exquisitely-rendered figures float on large banners suspended from the ceiling. The purposeful absence of a physical background references the ambiguity of border spaces, and also emphasizes the men’s iconic presence and ascension into a sexual- mystical realm. Alida Cervantes situates desire in brightly-painted arcadian landscapes based on the typical formats and themes of 18th-century Mexican casta paintings. These colonial prototypes illustrated the process of mestizaje, and attempted to locate race within the constructs of skin color, costume, objects, and actual landscapes and domestic spaces. But in Cervantes’ lush and remote settings, colorful men and women of mixed races (castas) playfully and privately battle lust, physical instinct, and temptation. With titles like, Criolla considerando las consecuencias de cojerse a un charro ladino, Cervantes seemingly avoids the seriousness of much post-colonial discourse, while still addressing the extremely complex relationships between race and sexuality.

The ontological emphasis of this year’s SUR was most clearly expressed in the object-oriented exhibit at Cerritos College. Questions of the nature of physical objectivity, space, existence, and change are posed in works such as Andres Payan’s Geophagy, 2011, a video featuring the artist eating dirt from his childhood home of Ciudad Juarez. While Payan considers the dirt of his homeland and receipts from his twenty-two border crossings as physical evidence of the spaces he has inhabited and traveled, Matt Lucero constructs and commemorates the traces of physical presences-- train tracks, his grandfather’s labor, the path of the train itself. Adriana Baltasar’s crocheted street signs and weeds (dandelion, chicory, and thistle, 18th street Immigrants, 2011) demonstrate the beauty and resilience of alien objects adapted to new terrains. Through layers of extensive research and careful analysis, Gala Porras-Kim creates objects that visualize sound, phonetics, language, and “the impossibility of translation.” Cognate Collective’s Borderblaster (Cerritos), 2013 is a portable listening station that maps the sound of SUR’s space and time, specifically, of the one hour and fifty-four minute commute and radio-signal range between San Diego and Cerritos.

Regarding borderblasting, it is interesting to note that the closing of the 2013 SUR Biennial almost coincides with the 20th anniversary of the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement. While NAFTA’s goal was to eliminate barriers to trade and investment between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, its passage further complicated the already ambiguous relationship between the U.S. and regions south of the border. NAFTA’s globalizing effects were immediately and most obviously felt in the rise of the maquiladora model of manufacturing in a free-trade zone, resulting in the Zapatista uprisings, the rise of drug cartels, and drastically-revised immigration policies. These developments and continuing responses to NAFTA over the past twenty years have contributed to the muddling and perhaps nullification of the geographical and ideological constructs of Latin America, Made in Mexico, Made in Los Angeles, and even the broad category of SUR. Since the 1990s, the increase in art fairs and biennials in Mexico, South America, and regions in the United States where there is a strong Latin American presence has resulted in a transnational mode of Latin American artistic production and a nexus of exchange in which the specificity of physical location and place of origin has apparently lost its relevance. In their de-emphasis on personal/cultural identity and focus on modes of objectivity, this year’s SUR artists strategically place themselves in a position of simultaneous critique and participation in this global politicking. As a founding member of Border Art Workshop, Tanya Aguiñiga established a community center in Maclovio Rojas, an autonomous area of Tijuana surrounded by maquiladoras. All of the town’s buildings were made of trash from the United States. She recently founded Artists Helping Artisans, and has collaborated with various weavers and textile producers, including the Zapatista Women’s Weaving Collaborative. For the Rio Hondo Gallery, she wove a multicolored tapestry of cheap Mexican blankets that provides both a stunning visual commentary and a beautiful solution to some of the problems associated with continental American trade, production, exchange, and labor. Break + Pausa’s Test Kitchen performance at Cerritos College opened up a community dialogue about working the restaurant line. It is very fitting that TAM featured a video project by Yoshua Okón, one of the founders of Mexico City’s legendary Panadería, an experimental and highly influential gallery space and residency program set up in an old bakery in the 1990s. In 2009, Okón founded SOMA Mexico, a nonprofit artist-run space and living laboratory that sponsors weekly artist talks and conversations centered on the community. In a recent interview, the artist emphasized the importance of community-based projects: “Culture does not get generated in isolation. Culture gets generated in interaction.” There is a notable level of anonymity and generosity in the actions, objects and images of SUR. Daino’s Suprematist guerilla-style graffiti, To Whom it May Concern, exemplifies a Zapatista spirit in the participatory sense; installed from the roof of a building at Cerritos College, it is both a gift and message for any and all who might listen.

Cynthia Neri Lewis

Rio Hondo College

Stay Connected